When my mother was young, before she was my mother, she was an artist who worked primarily in traditional printmaking techniques like etching and lithography. For a number of years, she made enough money to live off of by selling her prints, and making candles. I know that, at the time, she made her own clothing. And she didn’t own a car (she biked everywhere). It was the late 1970s and early 1980s, in Kalamazoo, Michigan and being alive was pretty affordable. But despite all of that, I sometimes still marvel that she was able to make a living on prints and candles!

Then, she had me. Not long after that, my father effectively disappeared from the face of the earth and my mom realized that she was going to be raising me on her own. She went back to school, became a teacher, and stopped making art. Or, at least, she stopped making art to sell (my childhood, and her classrooms, were fully decorated with my mother’s art). When she finally got back to making art again, she decided to work with clay (like her own mother had).

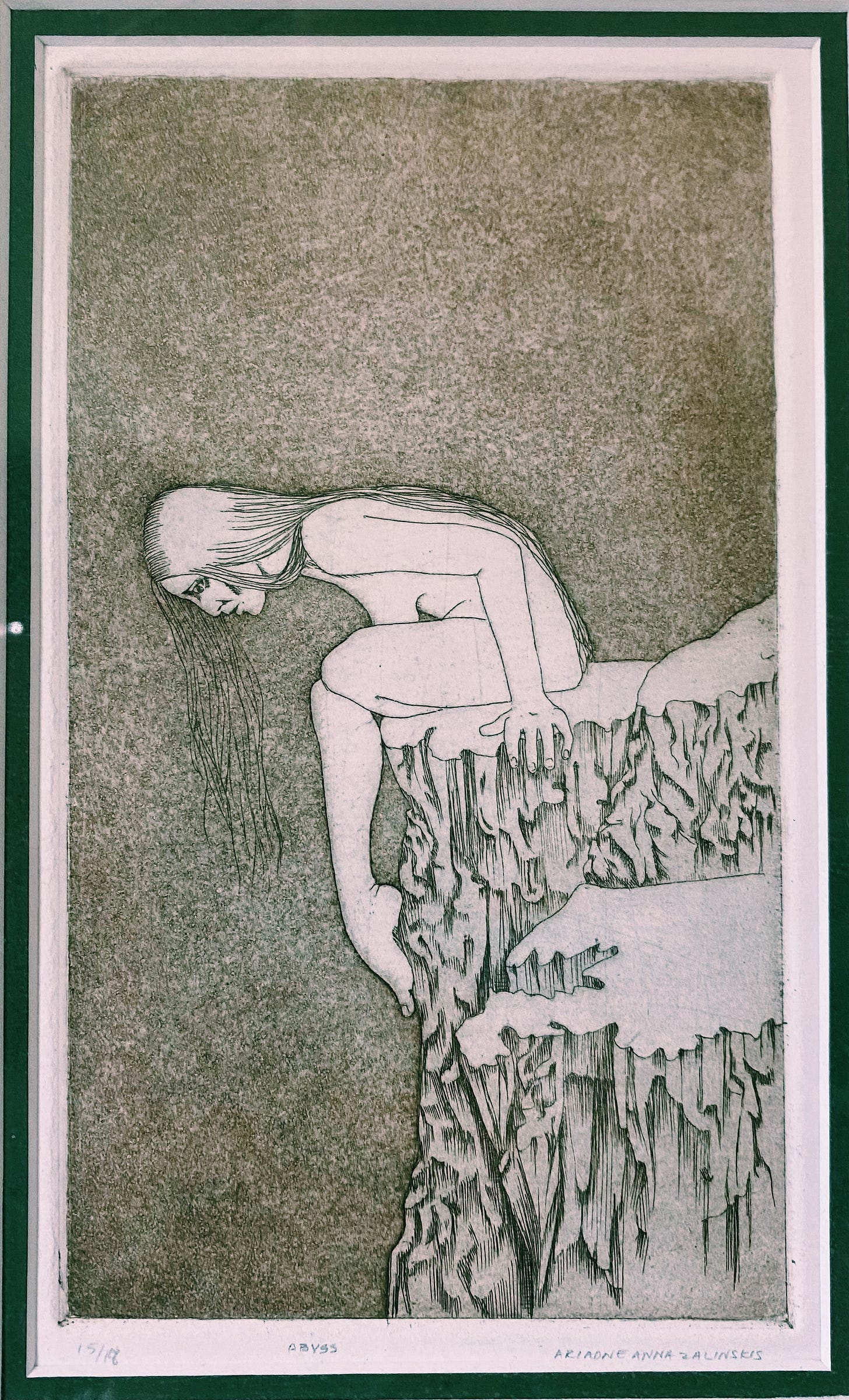

When I moved into my own apartment, during my last year of college, my mom gave me a series of framed prints that she’d once made. It was a kind of housewarming gift. I recognized them from one of the walls in one of the many apartments we’d lived in, during my childhood. I hung them in my new apartment, and the series has had a place on my walls for the past twenty years or so. When I lived far away from my mom, in Maine, or Vancouver, or New York, or North Dakota, the images have been a daily reminder of my mom’s stabilizing presence in my life. But they’ve been more than that, too. They’ve been like a little philosophical meditation on who I am, what sort of people I come from, and what they’ve taught me.

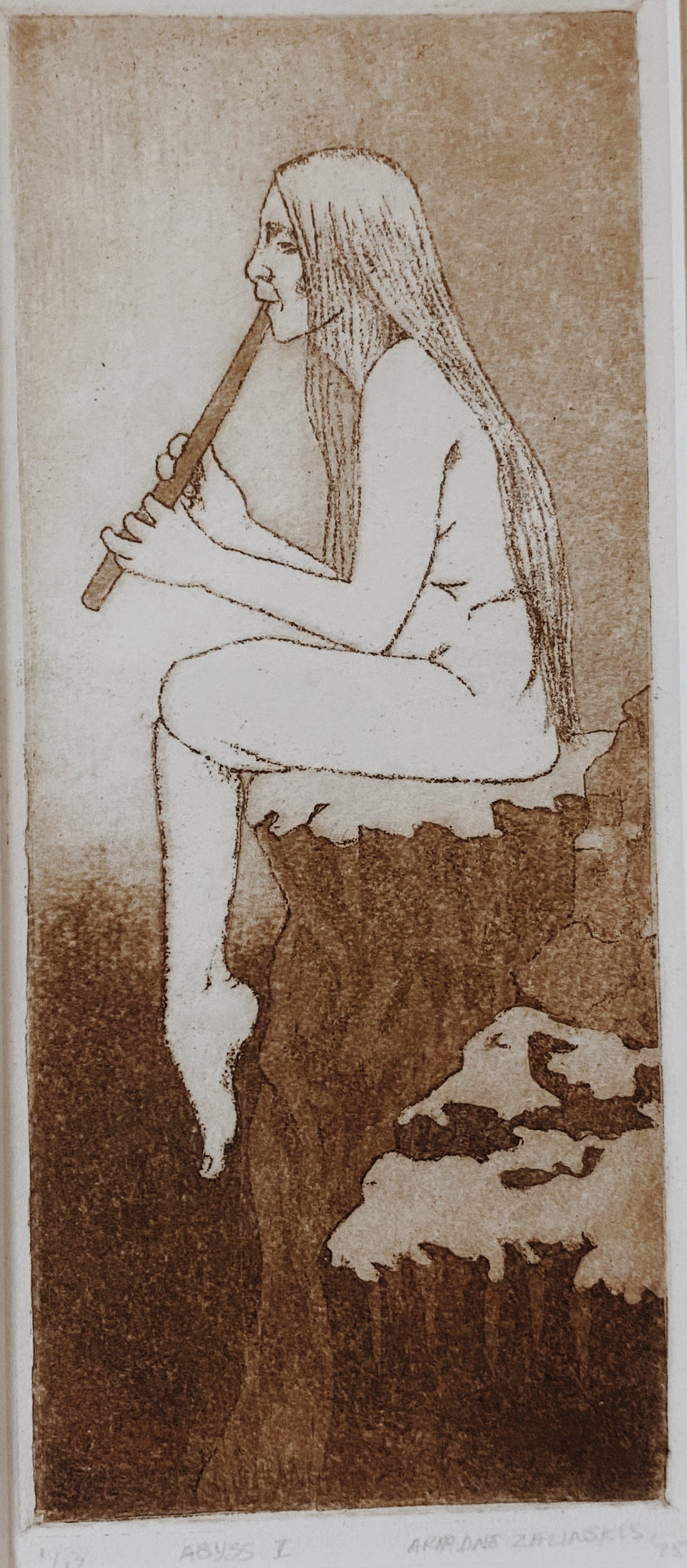

The series is called “Abyss” and the first image in the series is of a woman (roughly a self-portrait) sitting on the edge of a rocky cliff. She’s looking down below her, and her expression is suitably perplexed. But the tone of the image is warm. It’s a woman looking into the abyss, curiously. She doesn’t appear to be in any imminent danger. In fact, it looks like she’s probably put herself there, at the end of the world. The other two images are the same figure, at the edge of what looks like the same cliff, playing a flute. Making music at the edge of the abyss.

I’ve always been a very serious person who refuses to take things at face value. In the preface to Sister Death, I wrote about the fact that I’ve been meditating on death, mortality, and whatever it folds into since I was at least three years old. I think the most common description I’ve heard people use for me, across the course of my life thus far, has been “intense.” I will admit that, from time to time, I’ve felt a little guilty when I hear people describe me that way. I’m not immune to the gender politics that make women feel as if they should be, above all else, “nice” and “agreeable.” Intense sometimes feels like an inappropriate thing to be, and I know that the description is often a negative judgement. But my mom’s image of a woman, staring into the abyss and making music, has always been a comforting reminder to me that this is just who I am.

Part of what comforts me is the knowledge that I’m not some strange anomaly. I’m part of a little community of deeply intense people: my family. It’s a family full of intense people who channel that intensity to make art. When I look at the image, I remember that there are people to whom I belong.

The matriarch of this community of intensity was my grandmother Maiga. She was an artist who drew, and wove on a loom, but worked primarily with clay. This is an iconic image of her, in my family. It was taken in the displaced persons camp in Germany, where she lived with my grandfather, great-grandmother, and her six children after she fled the Russian occupation in Latvia and waited to come to the U.S.. Her seventh child was born in America. I believe that the person who took the photo was my uncle Egils—a photographer who started taking pictures when he was a teenager, living in the camp.

The image you see above is used in a work of art from our family friend, Sniedze Rungis, another Latvian immigrant who ended up in Kalamazoo with us. The landscape at the top of the image illuminates the silhouettes of trees, in Latvia. It’s from a photo Sniedze took after traveling back there in the 1990s. My grandmother never lived to make it back, although her ashes are buried there now, in a wooded cemetery. In 2007 my mom and I traveled to Latvia, and one of the places we visited was this cemetery.

In the image my grandmother was probably a little younger than I am right now. And she was living as a refugee, in a room in a barrack with her seven children, waiting to become an immigrant. When I’ve gone through what feel like difficult periods of my life, especially since becoming a mother, I’ve sometimes found it helpful to compare my situation with hers, to put things in perspective. And I’ve always found it helpful to think about the cheekiness, and the intensity, of the performance she’s putting on in that image. How much it doesn’t feel, when I look at it, like she’s the mother of seven kids living in a displaced persons camp. It feels, to me, like a version of making music at the edge of the abyss.

There’s certainly a deep undercurrent of anxiety that runs through the people in my family. I remember that, growing up in Michigan, my grandmother was completely terrified of tornadoes. They were one of the things in the new country that were alien and unmanageable to her (like driving a car). There’d been a particularly devastating tornado the year before I was born, in 1980, that hit the downtown and left much of it destroyed. So that probably didn’t help my grandmother’s anxiety. Nevertheless, the kind of anxiety she would display whenever the news announced a tornado watch (which was often) seemed completely off the charts to me, as a kid. If we were playing outside, we would be called in immediately, where we would be obliged to sit in front of the TV and watch weather reports with my grandmother until the watch or warning passed. My mother clearly struggled with anxiety, as I was growing up. And I’ve gone through some periods of my life where my own anxieties have felt so omnipresent and oppressive, it’s been difficult to see anything through them.

I think that this is the obvious down side to living here, on the edge of an abyss.

But as I’ve been getting older, and especially over the past several years—March of 2020 was a real turning point—I think that the fragility of things (the fragility of this whole enterprise we call life in America) has become much more undeniable to me. The reality of pandemic, the horrific violence at the heart of American life that just won’t dissipate, the pressing changes that climate change is creating: all of these make this moment feel so incredibly fragile. There is a part of me that wants to deny that fragility, to pretend like it’s possible to create some fortification that will allow us to continue living as if it didn’t exist.

The better part of me, though, is finally ready to recognize that I’m just catching more and more of a glimpse of that abyss I always sensed was there, all along. I have no idea what’s there, when I look down into it. That’s the nature of an abyss. I know that there are things in it to be afraid of. I know that it might send us on journeys that we don’t want to make. But I also know that there are beautiful things there, too. I feel like I’m ready to accept the gifts that I’ve inherited: that capacity to make art, and drama, in the midst of the fragility of things. I’m acutely aware of the fact that I can’t predict what’s ahead. I hope that I’m at least a little prepared. More, I hope that, especially as a mother, I can find a way to make art—to make life beautiful—wherever we end up. To make art out of whatever life we find ourselves in, like my mother did, and her mother before her. I feel more and more confident that whatever happens, there will always still be enough joy and beauty to do so. I’m grateful for the inheritance that gives me a sense that it’s possible—to make music, even at the edge of an abyss.

Sending you the strength of a thousand mothers today.

By the way, last summer my mother published a short collection of my grandmother Maiga’s stories. She recorded them, on a cassette tape, when she was sick with cancer at the end of her life. Over the course of more than twenty years my mother translated them into English, for those of us in the family who don’t speak Latvian. My cousin Lea, a brilliant artist who works primarily with cut paper, created art for the book. You can read about it/listen to an interview about it here.

What a beautiful and thoughtful history. I remember your mom as I knew her through art, walking, talking and friendship. You are a gift of love to her. Best wishes, Lauren L

Wow, the prints are beautiful. And Latvia? I spent a sabbatical year in Riga! One of the most wonderful, and strange, experiences of my life.