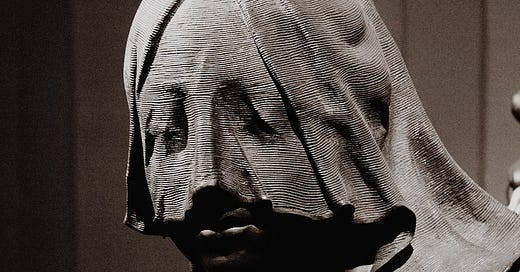

What I’ve Been Doing With My Primal Grief

On the everyday violence of American life, and the powers of mourning that might be a tonic

There are portions of my book, Sister Death, that are preoccupied with what most people would recognize as politics. In my view, of course, the whole book is political. How we think about death is political! But I recognize that, for many, our views on death have no clear policy implications and might seen as more “philosophical” than anything else. But there are portions of the book where I discuss, more explicitly, how our views on death can impact things like abortion.

I don’t write about this aspect of the book much, here on my Substack. I’m not entirely sure why, but I think it has something to do with the fact that it leaves me feeling pretty bleak. When I sit down to write something for this newsletter, I’m always trying to find at least a little beauty to illuminate. It’s as much for me as it is for you.

But I’ve been writing a series of essays for Religion Dispatches (RD) in which I’ve been discussing these explicitly political aspects of the book. The first of these essays was just published, this week. You can read the whole thing, here. It’s actually an essay, written in letter form. It’s a letter to my fellow Americans, about the fear that many of us are living in, as if it were a state of nature. And about how many people are responding to that fear by arming themselves against it. And about the primal grief I’m feeling over the violence all around us that can’t be metabolized.

In this space, this week, I want to spend a little time reflecting on how the piece came about, why I wrote it, and what feels clearer to me now that I’ve written it. Among other things, it’s left me thinking quite a bit about grief and the powers of mourning.

Weighing in on the Great Gun Debate

The other essays that I wrote for this series are topics that I pulled more or less from the book itself. They aren’t quite excerpts because I’m not cutting and pasting passages from the book. But I am recycling ideas that I develop in the book. I will post links to those pieces, once they’re published. But this first essay (which was actually the last one written) is different. It’s about fear and guns, in America.

I was in the midst of writing about something else (human composting, in fact) when the school shooting happened, in Nashville. It seemed as if it was all anyone was talking about, for several days. My editor at RD - Evan Derkacz - contacted me to see if I had something to say about guns and death in America, and if I could write about it.

My initial impulse was to say “no”. I didn’t write about guns, in the book. And I don’t speak much, publicly, about gun politics. I’ve never felt like I have anything to add to the conversation. I want to see more legislation that will stop the proliferation of firearms. I want to see an end to these mass shooting events. Nothing about my position is unique. I want what about half of Americans want.

Then I started to think a bit more about it. Was it really the case that I had nothing to say? Or was it simply the case that I hadn’t wanted to think about it? A couple of weeks later there was another mass shooting, here in Louisville where I live. It was several blocks away from where my daughter was in school. I decided to weigh in.

Gun Politics and Mass Death

In Sister Death I write about what the philosopher Edith Wyschogrod called “man-made mass death.” She argues that since the mid-20th century, we’ve been living with a new form of death, one that’s enabled by and makes use of our technologies in order to exponentially increase the scale and scope of death-dealing. Our guns and bombs and other weapons of mass destruction have made once unthinkable forms of death possible.

I would argue that this form of mass death extends further back in history than the 20th century, and that it’s a key dimension of the forms of mass death that accompanied colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade. But I agree with Wyschogrod’s claim this form of mass death would have been unthinkable for our ancestors. This includes philosophical ancestors like Socrates. For thinkers of the past, she argues, our contemplation of our own mortality was a source of authentic meaning and possibility. Our sense of mortality helped us to remember the fragility of life, and this could be a reminder to embrace the precious and impermanent present. But today, in a world of manmade mass death, we experience our mortality very differently. If we aren’t careful, we might start to contemplate our mortality and never find a way back up to the surface. There’s just not as much life to hold onto.

I consider American gun politics to be very much a part of this world of manmade mass death. The kinds of assault weapons that more and more Americans today are carrying are little weapons of mass destruction. They are part and parcel of this world of manmade mass death. I initially felt like this was the only insight, from Sister Death, that I could bring to this conversation. Guns in America are pulling us deeper into this world of manmade mass death.

But I didn’t want to write about something so irredeemably bleak. I didn’t want to feel myself sinking into it.

Then I remembered another thinker I write about in Sister Death. The multispecies anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose also wrote quite a bit about death, and mortality. She was concerned about human relationships with the more than human world, and she was especially concerned about mass species extinction. She worried, of course, about what this was doing to more than human worlds. But she was also concerned about the social, political, psychological, and spiritual impact that extinction events were having on us as well. She, like Wyschogrod, observed that in the present we are living into forms of death that would have been unthinkable in the past. The name she gave to this new form of death was “double death.”

Death in the past was part of an ecological cycle, Rose observed. Life and death worked in a kind of collaboration. Decay, for instance, was necessary for the germination of new forms of life. But capitalism, and its proliferating products and technologies, have changed things. Life and death no longer work together. Instead, death keeps proliferating and reproducing, and this proliferation is killing off life itself.

Rose’s view is also, undeniably, bleak. But there was something else embedded in Rose’s work that helped me shift perspective.

How Powers of Mourning Can Be a Tonic

One of the observations that Rose makes about the long history of life and death is that we—humans—have created methods for weaving life and death back together so that they can each become part of the fabric of our experience, rather than an irredeemably tragic disruption of it. This doesn’t take the pain of death (or life!) away, but it does serve as a reminder that together we can work to usher one another through the tragic ruptures, and onto the other side.

One of the key methods we have for doing this, she argues, is through our burial rituals. When we come together, communally, to recognize the end of a life and to help that person become an ancestor we are illuminating the tender bonds between life and death. Not the ways in which they do damage to one another, but how they collaborate to create ongoingness. This is what I call the sisterhood of life and death, in Sister Death.

Death is something we have always had to cope with. And it’s never been easy. No culture in the world has developed a method for making the fact of death painless, or even neutral. But we have developed so many varied ritual methods for grieving and mourning. In my class on death and the afterlife, this is actually one of the most uplifting things we talk about, believe it or not. Part of the reason is that we get an interesting window into other cultures, when we learn about how they care for and bury their dead. It’s illuminating! It’s a reminder that things can always be better, or more beautiful. Or stranger.

I think another part of it is that many of my students feel validated, in powerful ways, when they realize that grief is real and essentially universal. Many of them have been taught to hide it, or be ashamed of it, or to pretend as if being “strong” or “normal” means burying or sublimating whatever grief they feel. They don’t know what to do with the grief they bear. There’s nothing like a burial or mourning ritual to show you how powerful it can be to work with (rather than against) our grief.

The work of mourning is powerful, and transformative. It doesn’t make pain disappear. It doesn’t cure or solve anything. But it transforms something. It calls other people in, it brings them toward you. It clears a space in our shared worlds—our publics, our communities—so that we don’t forget about what’s gone missing. So that we remember the way in which those who’ve gone live on in our bones and hearts. This creates spaces inside of us, where those who have gone can continue to fill us with their love and power.

The letter that I wrote was an exercise in mourning. It was a lament. I don’t know how to speak to my fellow Americans who respond to their acute sense of fear by purchasing firearms and dealing more death in a death-saturated world. But I wanted to try. I want to believe that if we can make more space for mourning, and for the primal grief that just seems to be accumulating (especially since the pandemic began), that we might start to weave life and death back together again in a world where it sometimes feels impossible.