Tech is the Scapegoat? On Peter Thiel’s Political Theology

I looked into it, so you don't have to

I’ve been listening to a lot of podcasts lately; as if mainlining hot takes during my commute will somehow give me a sense of sanity in the midst chaotic uncertainty. Perhaps I’ve been out there searching for a good take. But, instead, I’ve been hearing about a lot of things I’d care not to—like Peter Thiel. As one of those shadowy figures who is both loosely, and obviously, bound up with the new administration he feels weirdly unavoidable now. I’ve heard a number of people mention, offhandedly, that he’s really been leaning into his Christianity lately. That didn’t interest me much. But then I heard someone mention his political theology. And that made me curious.

As someone who’s written a book on political theology (among other things) I felt a kind of professional obligation, or maybe just a morbid curiosity, to better understand Thiel’s political theology. Among other things, it’s helped me understand why claims like Ross Douthat’s—that the Trump movement is about widely shared populist ideals rather than oligarchical self-interest—just sounds so unbelievable. Thiel’s political theology makes it obvious that weaving what could be disparate ideological critiques together into a simple and comprehensive whole is absolutely essential to oligarchical self-interest.

What is Political Theology?

Trying to decisively answer this question, in a little Substack newsletter, would be a fool’s errand. Scholars in my field have been engaged in all kinds of debates about this topic. So I don’t intend to offer a wholesale definition of the topic. But I will tell you how Thiel seems to define it, and how that compares with the way I use the term.

The most explicit conversation about political theology that I could find was probably Thiel’s April 2024 interview with Tyler Cowen, where he seems to be describing political theology as a kind of theory of everything. Thiel expresses frustration at the way that our world of hyperspecialization seems to prevent us from taking a step back, in order to understand the “big picture.” He seems drawn to political theology as a method for tying together pretty much everything (economics, science, technology, culture, religion, etc...) into a package that fits seamlessly together. Political theology is a kind of ordering system that Thiel seems attracted to because he’s lost faith in other dimensions of knowledge and discourse. Having a political theology, for Thiel, seems to mean having a big picture take, rather than a little scrap of a snapshot.

When people hear the term “theology”, they might have mystical or spiritual associations with the term. If theology is a theory about God, or the divine, it might seem to draw us in that direction. But that sort of mushy stuff appears not to interest Thiel in the slightest. He seems totally uninterested in metaphysical questions about the nature of God, and even less interested in spiritual questions (how God might provide comfort, etc...). He’s apparently described himself as “religious but not spiritual.” For Thiel, political theology seems useful primarily as a critical or diagnostic tool.

His sense of what political theology is, what it’s for, or what it can do, seems to be pretty directly formatted on the work of the German legal theorist (and, famously, Nazi) Carl Schmitt. Schmitt’s sense of the political boiled down to the friend-enemy distinction. The state, for Schmitt, was the fundamental shape of the political, and the most basic or elemental political distinction was the determination of who your friends and enemies are. The rest is details. When Thiel talks about political theology (or even just politics), he does seem pretty centrally fixated on delineating who his enemies are. That seems to be his most immediate big picture need. He wants to isolate his enemies, and lump them together in a kind of coalition of the satanic.

My sense is that, for Thiel, political theology is primarily an intellectual tool for cutting through the insane complexity of modern life, and the many excesses in our information society. Political theology is an ambitious but also intellectually aloof method for telling a very big story. The storehouse of religious or theological images, ideas, and metaphors, becomes a resource for these stories. But not a spiritual resource. Rather, these resources serve as evocative images and metaphors that one can use to describe or characterize their enemies (and, if they have time, their friends).

I have to confess that it was a little uncomfortable for me to realize how much overlap there is between Thiel’s definition of political theology and my own. I don’t really want to feel any intellectual resonance with this guy. But I’m also drawn to political theology (and theology more broadly) because of its disciplinary promiscuity. Unlike many other specialized academic fields, theology does offer an incredibly generalized perspective with a lot of disciplinary blending that no one really polices. I don’t see political theology as a big story about gods, but I do tend to think of it as a story about something (like a powerful idea) that seeks to be as big as (or almost as big as) a god. Political theology is a big story about how power works, and a theory about what happens to those who get close to it.

I understand how anachronistic and problematically universalizing political theology can be, in the world we live in today. Especially on the left. Political theology is exactly what one should no longer be doing. And I think that’s probably one of the reasons it appeals to Thiel. But I don’t think that he’s the only one who keeps wanting the sort of story that political theology can tell. I think a lot of people are hungry for this sort of story, even if only in their secret heart. And you can turn almost anything into a political theology of sorts, if you look at it long enough in the right light: psychoanalysis, Marxist thought, AI, raw milk, whatever. Which is why, despite some misgivings, I still find it useful to understand political theology.

Who is His Enemy? Who is His Friend?

Thiel really enjoys the use of anachronistic figures from Christian theology. Talking about Satan, the satanic, and Armageddon probably gives a pseudo-prophetic contrarian vibe in his social world, which I can imagine that he relishes. These figures also give him an evocative organizing strategy for demonizing his enemies. He argues that too many people are obsessed with the end of the world (and the things that will end it) and not focused nearly enough on the rising antichrist.

The most satantic thing of all, for Thiel, is probably the figure of a one world government. This seems to be the thing that that this libertarian most dreads, and believes would lead to the most disastrous possible outcomes. One world government is basically the anti-christ. And Thiel seems to find this one world government to be an increasingly real, and threatening, possibility. When Tyler Cowen presses him a bit, asking if (especially here in the United States) we might actually be pushing toward greater feudalism, Thiel minimizes this. “It seems that we’ve gone far more in the peace-and-safety direction than the global-chaos direction,” he argues, noting how difficult it’s become to even own a Swiss bank account these days.

Those who are neatly aligned with the satanic—Satan’s minions here on earth—are, perhaps predictably, “the woke.” Thiel suggests that it would “pay a lot of dividends” to really think through the relationship between wokeness and Christianity. In his telling, wokeness looks deceptively Christian because it takes the side of the victims. It’s “downstream” from the Bible in that sense, he notes. And yet, he claims, it’s nothing but a vision of original sin with absolutely no possibility of forgiveness. Wokeness has no mercy. He describes Elizabeth Warren, for instance, as essentially a Puritan minister from the period of America’s greatest religious intolerance. So he feels compelled to call wokeness out for its sneaky hypocrisy—it’s a false Christianity, a satanic trick of the imagination.

Thiel is characterizing wokeness as part of what his theory hero—the French thinker René Girard—described as the deceptive modern concern for victims. Much has been written about Thiel’s obsession with Girard’s work, especially an idea that Thiel called mimetic desire (John Ganz has a nice series of Substacks on this that starts here). But I’m going to stick with the explicitly theological images and symbols, to keep things simple. “Our society is the most preoccupied with victims of any that ever was,” Girard argued in the early 2000s. “Even if it is insincere, a big show, the phenomenon has no precedent. No historical period, no society we know, has ever spoken of victims as we do.” But Girard believed that this was nothing but a social competition: an attempt to compete for social prestige by displaying more concern for victims than your rival does. It’s ruthlessly self-critical and it never ends: it has no mercy. Girard argued it was nothing but a pathetic “secular mask of Christian love.” What this modern concern for victims lacks, or can be remedied by, is what Girard describes as the “Gospel stance” toward victims. The secular concern for victims must be remedied by Christianity, in other words.

Interestingly, for Girard, the Gospel stance does not seem to be primarily directed towards displays of mercy. Instead, Girard argues that what we see emerging from the Gospels is the “heroic resistance” of a “small minority” that is brave enough to resist a violent (satanic) contagion in the social world around them. The Gospels—a picture of the small early Christian movement—illuminate the bravery and heroism of a kind of spiritual oligarchy, we could say. I suppose that Thiel imagines himself as a prophet of anti-wokeness who is part of this little oligarchy, fighting the mass (and disingenuous, even satanic) contagion of wokeness.

Of course, Thiel’s list of enemies is longer than merely the woke. Wokeness is part of a larger coalition that Thiel codes with the film of the satatnic. The problem with this coalition is the way it pulls towards a one world government (or, the anti-christ). I suppose that we could even include science and scientists among this coalition.

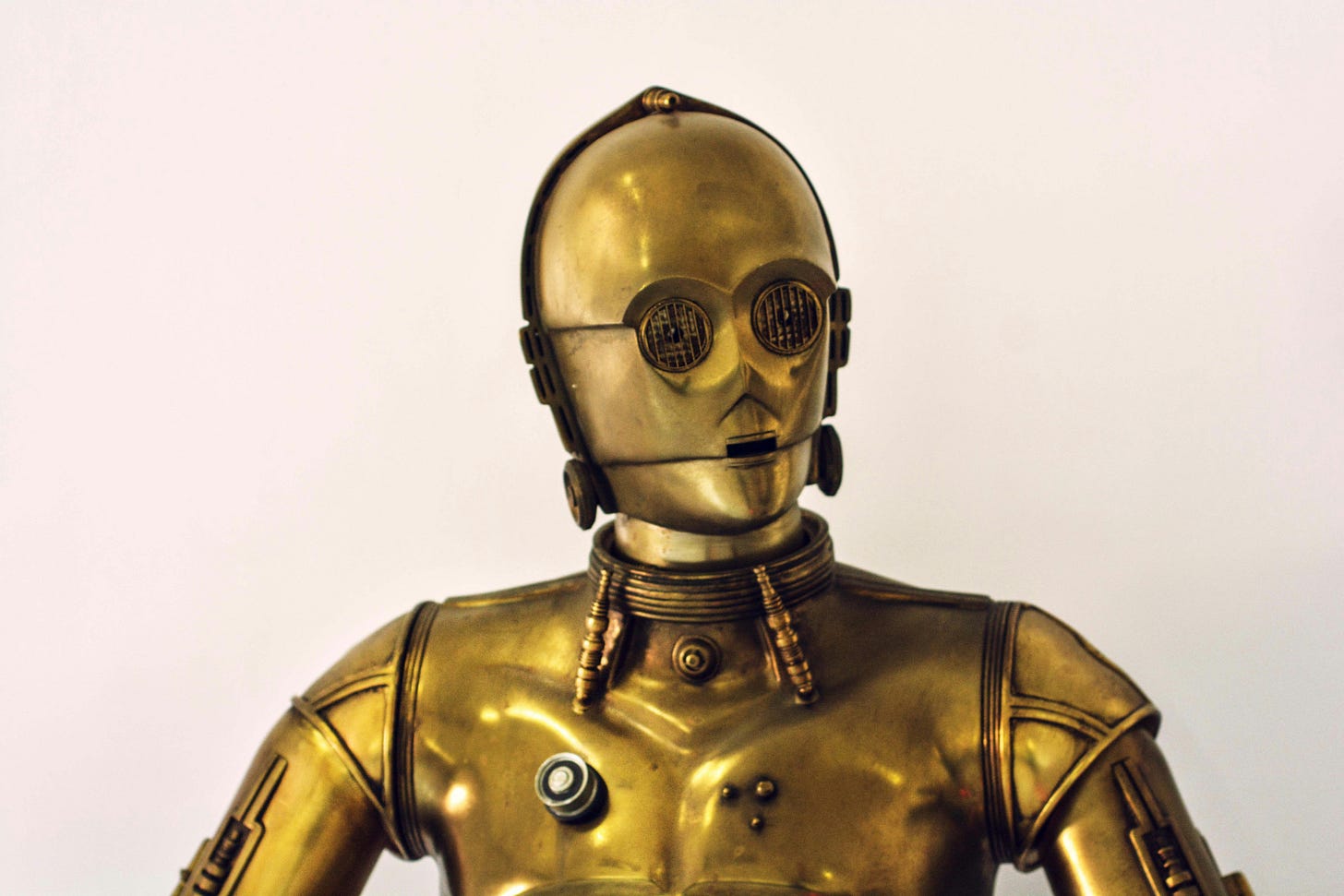

Thiel seems nostalgic for early modern science, characterizing the science of that time period as establishing itself in a “two front war” against dogmatism, on the one hand, and excess skepticism on the other. He believes that science, as he sees it being practiced in places like the US today, is myopically focused on combatting excess skepticism and, for that reason, has become too dogmatic. He reflects, with nostalgia, on the early modern scientist’s experiences of wonder and then points to contemporary graduate students in the scientists who—he says—are not immersed in wonder but instead have become like “indentured servants”, or mere robots who are expected to fall in line with the program (presumably whatever the one world government, or anti-christ, wants). Far from considering science to be the crown jewel in American educational systems, Thiel seems to relish the possibility of seeing scientists humbled. One of the ways he thinks that scholars in the humanities are “better off” than scientists, he chides, is that “at least they know they will be unemployable. Whereas, it takes a scientist to be deluded into thinking that they will be taken care of by the natural goodness of the universe.” He seems to be working with the new administration to ensure that this is no longer the case.

I’m sure that I could create a longer list of enemies, but I hope you get my point. Thiel’s political theology creates a general framework for gathering together a political coalition of problematic actors who seem destined to suck the world up into a demonic one world government. What his satatnic coalition is opposed to doesn’t seem to be God so much as technology.

Thiel seems to be under the impression that Luddites wield an incredible amount of political power today. It’s the incredible power of the Luddites in the FDA, for instance, that stands in the way of creative forms of biohacking all over the world. And when it comes to AI, what scares him more than anything is the attempt to place limits on its use and development. Because if there were people who were powerful enough to stop AI, Thiel suggests, they would probably also be people who could destroy the whole world (agents of Satan), presumably through their one world government.

Thiel doesn’t seem to think that tech can save us per se. He does seem to think that human society is pretty much doomed. But tech looks like his best hope. If something like AI ends up rendering massive numbers of human beings incapable of contributing to our economy, and if it leads to even an even more dramatic increase in wealth inequality, this doesn’t seem to matter to Thiel at all. Because Thiel seems to believe that the real problem here is that our modern false concern for victims has generated so much resentment and dogmatism that we have begun to scapegoat the one and only hope we still have: technology. The truest victim of all, in this view, is technology. And Thiel’s political theology seems like a speculative and symbolically coded thought framework designed for the spiritual oligarchy who can step in to take charge over the masses, in order to protect the scapegoat.

Is This Even Worth Taking Seriously?

I can imagine that many of you who are reading this are having a difficult time taking this theory—this political theology that I’m drawing out of Thiel’s claims and statements—seriously. I recently saw an interview with Elon Musk’s daughter in Teen Vogue and she described this new administration as “cartoonishly evil”. I think the description is pretty apt, and the same could be said about pretty much everything I’ve laid out here. It sounds insanely reductive and sort of cartoonish to call wokeness (which is also a sort of cartoon figure) satanic. My analysis could very well be giving conspiracy theory vibes. So be it. I think there’s some value in the kind of connect-the-dots drawing that I’ve laid out here. At the very least, I think it helps to illustrate that, despite the tensions that might exist between a Steven Bannonesque populist arm of the new Republican Party and a Elon Musky tech oligarchy, there are people like Thiel who are trying to work out a more seamless fusion between the two. It gives us a better (if cartoonish) picture of the other side, I guess you could say.

In the end, though, I think that America is a country that loves its cartoons. I don’t think any critique of political theology will change that. Maybe it’s a legacy of that beloved old American technology: TV. Nuanced analyses of these cartoons only matter to a few of us who need a certain brain itch to be scratched. Perhaps the only thing that people will actually respond to is a more powerful, more inspiring, more enchanted, more humane, more merciful cartoon. We need an anvil to fall on this cartoon so that the Road Runner can run free and praise beauty of the desert, and the open road. Meep meep.

Speaking of Scapegoats populism and fear too please check out these references:

On the scapegoat drama

http://beezone.com/adida/there_is_a_way_edit.html

http://www.adidaupclose.org/Literature_Theater/scapegoat_intro.html

Populism and authentic politics

http://beezone.com/current/frustrationuniverdisease.html

http://beezone.com/adida/cooperation-and-doubt.html

The Ego, Fear & God.

http://beezone.com/ego-fear/index-47.html

Wow! That was a deep forest, and I was often lost in the bushes, but the trip was a trip! May I offer an alternative world? Since the Spirit of God is everywhere, Her/His mind is everywhere also. Make sense? Since both God and Her mind are everywhere, we must be somewhere inside that everywhere. Make sense? Since God’s mind is everywhere, then we must be living inside the Mind of God. Are you with me so far? If we are living inside the MInd of God, we must each be a thought God is having. If we are thinking the thoughts that God is thinking, we will probably be in a deep harmony with God and actually feel it as peace and joy. If we are thinking thoughts that God is not having, like our own thoughts, we will probably be feeling a dis-harmony, which will eventually lead us into a lack of ease…..a dis-ease. However, it is all taking place inside the Mind of God. Where else is there to be? Seems to me the only thing going on is: are we thinking our own thoughts or the thoughts of God? You tell me:)