Talking About Religion & Science, in Kansas

what happened when I gave a public lecture on my book

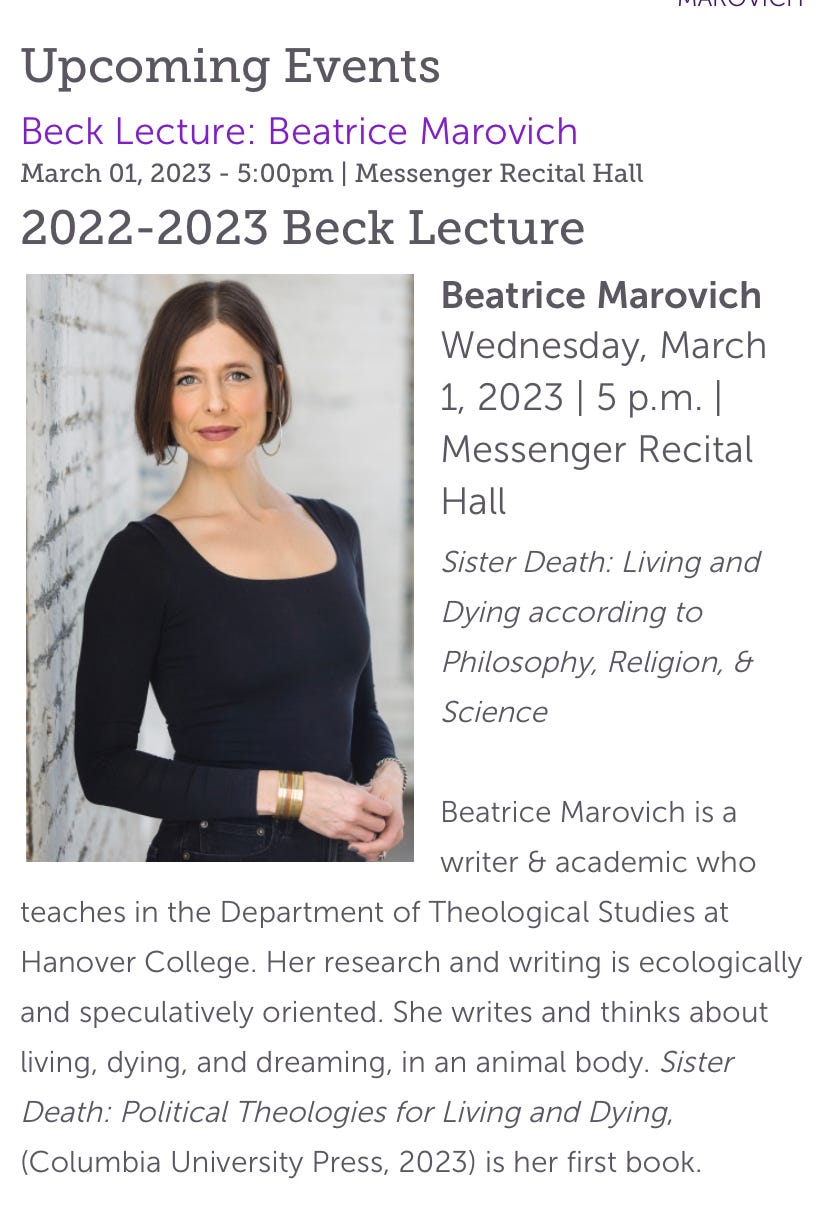

This week I was in Kansas: an hour south of Wichita, in the small college town of Winfield. Jacob Goodson, who teaches philosophy at Southwestern College, and organizes their endowed annual series of lectures in philosophy and religion, extended an invitation after hearing me speak on a panel at the American Academy of Religion’s annual meeting back in 2021.

First of all, before I say anything else, shall we just take a moment to appreciate those good people who, years ago, decided to endow a functionally unending lecture series in philosophy and religion? Southwestern is a tiny liberal arts college, much like the one I teach at. But we have nothing like this. Faculty in philosophy and religion don’t have a lot of nice things, these days. And it was a treat to be invited to Southwestern. The faculty and students were incredibly kind, and welcoming. My lecture was very well attended (many more people than I’ve come to expect at my academic conference talks!) They asked me great questions. And I Ieft with a lot to think about, and good feelings all around.

I was the third speaker in the lecture series, this academic year. My specific lecture— the Beck Lecture—was designed to be a talk on the relationship between religion and science. Jacob was telling me what he knew about the history of the series. Apparently the guy who funded the series studied with a Winfield professor of religion who’d traveled to Tennessee to testify on behalf of evolutionary theory, in the 1925 Scopes Trial. I’m honored to be kind of aligned with this guy, at some equally weird moment a century later in American history.

But, since I started writing my talk, I’ve been stewing over some things that I also wanted to think through with you.

How I Feel About “Religion & Science”

I spend a lot of time thinking and talking about “religion and science.” One of the reasons is that I teach a class to undergrads, on religion and science. Even during a semester when I’m not teaching this course, I’m always thinking about new ways to frame our conversations, the next time I do. In my research, I also think about a lot of themes—chiefly environmental—that ultimately intersect with research in the sciences. But, honestly, how many of us out there today—scholars in any field—are totally divorced from “research in the sciences”? Who isn’t kind of forced to contend with “research in the sciences”? Doesn’t “research in the sciences” impact all of us, on practical and theoretical levels, no matter what we think about and study today?

Scholars in religious studies who specialize in “religion and science” tend not to consider me someone who is veritably a part of their conversation. And, I’ll be honest, I don’t expend a lot of energy trying to prove that I’m a part of those conversations. Don’t I think that my book Sister Death is relevant to conversations in subfields like bioethics? Of course I do! And don’t I think that there are clear environmental consequences for the war against death that Christianity has inspired, in American culture? Of course I do! But what I dislike about conversations in “religion and science” is that they often tend to take the shape of apologetics.

You might recall my recent diatribe against apologetics. Ultimately, I think, I’m afraid of getting stuck in an apologetic mode: always working to defend something I’m not even entirely sure I want to defend. The subfield of religion and science tends to be fundamentally apologetic. The field exists, in large part, because of the reigning attitude of skepticism toward religious claims and ideas, in the sciences. Of course, the field exists in part in order to convince religious people that they should care about the sciences. But many academics who talk about religion and science aim their arguments toward other intellectuals, who are reluctant to take religion seriously. Many books on religion and science have been published that follow this simple formula: “you can believe in both God and science because _____.” And many of these books have been written by white male (Christian) scholars. It’s difficult not to think about this as a prestige contest, on some level.

So I sat down to write my talk, which had to—on some level—explicitly address the relationship between religion and science in my own on work. But I felt anxious about doing apologetics. Not only did I want to avoid getting stuck making the argument that you should still care about this work, even though it’s not “science”! More, I was anxious that I would spend so much time talking about this sort of thing that I would never get around to talking about what I actually have to say.

Biomythologies of Aging

The way I tried to avoid doing apologetics was to talk about an area of shared concern: something that matters in my own research, and in scientific research. What I chose to focus on was aging. This is something that I speak about with some frequency, in the book. If we think of ourselves as at war with death, I argue, then we are also at war with phenomena we associate with death such as aging, and decay. But I don’t speak in any great detail about aging, in the book, despite the fact that it’s clearly on my mind.

In Sister Death I make the argument that life and death are biomythical figures. What this means, for me, is that while they are clearly phenomena we can study biologically (and that impact biology) they are also deeply mythical figures. They are figures that we use to tell big stories about why we’re here, and what we’re meant to do while we are. Researchers working in the sciences are not immune to these biomythologies, regardless of their skepticism about religion, because these biomythologies often function subtly and symbolically in our broader cultural context. These biomythologies often borrow from religious discourse, but function as secular narratives. Aging, as a phenomenon associated with living and dying, is also biomythical. And researchers in the sciences are sometimes implicated in reiterating particular biomythologies, at the expense of others. That is, many researchers perpetuate the biomythology that we are at war with death, and at war with aging.

My biggest critical target, in the talk, was the debate that’s playing out in medical research about whether or not to classify aging as a disease. I think it goes more or less without saying that, in American popular culture, there’s an ongoing war against aging. Getting old is thought to be bad, being young and fresh and spry is good. Historically this has had a particularly devastating impact on women who are destined to age, yet expected to maintain some semblance of their (fertile) youthful appearance. It’s a legacy of our reproductive politics. But I’m pretty sure that all of us who are aging in America feel, on some level, that we are locked into a state of irreversible decline. For decades there have been researchers in the sciences dedicated to discovering a “cure” for this terrible predicament.

The motivation for this isn’t vanity, to be fair. Many researchers who want to classify aging as a disease have targeted aging because it tends to be a major risk factor for a host of illnesses. And I don’t want to appear callous, as if I’m not in favor of finding new ways to care for one another in difficult circumstances. I am entirely in favor of making aging as painless as possible for anyone going through it. But I think that pathologizing aging is a mistake. It creates a battle where I don’t believe we should create one. I’m not alone in this, of course. There are plenty of medical researchers who are entirely opposed to the classification of aging as a disease, because of the possibility that this sort of discourse could cause “real world harm.” Nevertheless, the conversation endures.

Transformations

Disability studies offers an especially profound critique of the real-world harm that pathologizing aging can do. As Joel Michael Reynolds and Anna Landre have argued, ageism and ableism are interrelated phenomena. And one of the ways that ageism often manifests is as a form of ableism. People don’t want to age or grow old because it might mean becoming disabled. Indeed, Reynolds and Landre argue that, if we live long enough, disability is inevitable. In this sense, disability is part of our human journey. It’s something we will all experience, if we live long enough. “Disability is an integral and essential part of what it means to be human,” they write.

They also reflect on the fact that disability—learning to live with various forms of disablement as we age, for instance—is part of a transformative experience. These kinds of experiences change who we understand ourselves to be, and how we live in the world.

Transformative experiences can be devastating, especially if our cultural context does not hold open a space in which to recognize and honor these transformations. When we live in a culture that warehouses people, as they age, and stigmatizes them for displaying signs of aging, we set the stage for a devastating transformation. When we declare that aging is a disease we are at war with, we set the stage for a devastating transformation. It’s a war we won’t win. But when we can recognize that aging is a complex biomythical process during which the biological changes we pass through can also trigger deep psychological and spiritual changes that can allow us to experience the world in profoundly new ways, we can set the stage for a different sort of transformation.

I don’t know that it matters, in the end, whether researchers in the sciences who study gerontology or who debate about the nature of aging take religion seriously. But I do think it matters that, as a culture, we refuse to reduce phenomena like aging to scientific or medical conversations. It is that, for sure. It’s inevitable that as we pass through the complex network of phenomena that we associate with aging, it will benefit us to have an understanding of biology and access to medical care! But if aging is, as I think it is, biomythical then we will also benefit from conversations about it that take it seriously as a social, cultural, psychological, and spiritual phenomenon.

Research in religion and theology can help, here. Navigating profound spiritual transformations (and evaluating touchstones and rituals for this navigation) is a consistent theme of research in this field. Work in disability studies, psychology, art, literature, history, and a host of other fields can also help. I may not be deeply committed to carving out public space for “conversations in religion and science.” But I am deeply committed to carving out public space for messy conversations, like this, about the biomythical phenomena that shape our bodies and worlds.