The Paleolithic cave art on the walls of the Lascaux Grotto in southwestern France was discovered by a dog. Of course, the dog was with people—four teenage boys, who explored the cave looking for treasure. It’s because of these four boys (not the dog) that we know about the art today. But I like to think of it as a gallery discovered by a dog. It lends to the powerful air of more than human mystery that surrounds this fantastic cultural-geological phenomenon.

Despite the fact that the art on the walls was created by humans, it’s so old that the humanity this art appears to give us access to brings us right up against the very edge of our sense of where, in time, human beings can live and exist. The art makes human life feel timeless: both more ancient and more new than it is. Being near this art can give you a clear and chilly sense that human life itself is always already more than that: bigger and wilder than whatever we thought was human, in time and space. It’s a reminder that—like the life of the gods—even human life is beyond what we can reasonably be expected to believe.

Lascaux (as well as a number of other Paleolithic galleries in France) is a space that’s become so powerfully more than human that most humans aren’t even allowed to enter it anymore. We could call it more than human, by law. And yet, Lascaux is still a major tourist destination, with as many as 4,000 visitors making a pilgrimage there each day in the high season. How can this be? What are the tourists coming for if they can’t even get inside of the cave?

They’re coming for a kind of virtual reality: a synthetic cave experience. This sounds like it would be a paltry imitation of the real thing, doesn’t it? But when I recently visited the “caves” at Lascaux, I found the synthetic cave experience to be a compelling, hyper-curated, virtual portal into a stream of Paleolithic time. The experience, to me, felt like a virtual encounter with sacred relics from a deep ancestral past: from a time so deep that it seems to predate whatever it is most of us have been taught to think of as human.

Creating the Seal

It’s not entirely clear how old the gallery of more than 600 images, in Lascaux, really is. It’s likely that some of the paintings there could have been created as long as 17,000 years ago. But the only pigment on the wall that can be reliably dated is the carbon, and not all of the paintings use carbon. However old the oldest paintings are, it’s probably the case that people re-entered the caves for thousands of years to view what others had created, and to add their own images. But the caves were probably sealed off, through some sort of natural disaster, about 12,000 years ago. This left the images untouched by human hands and human time until 1940, when a dog (and his boy) discovered a hole in the earth, left behind by a fallen tree.

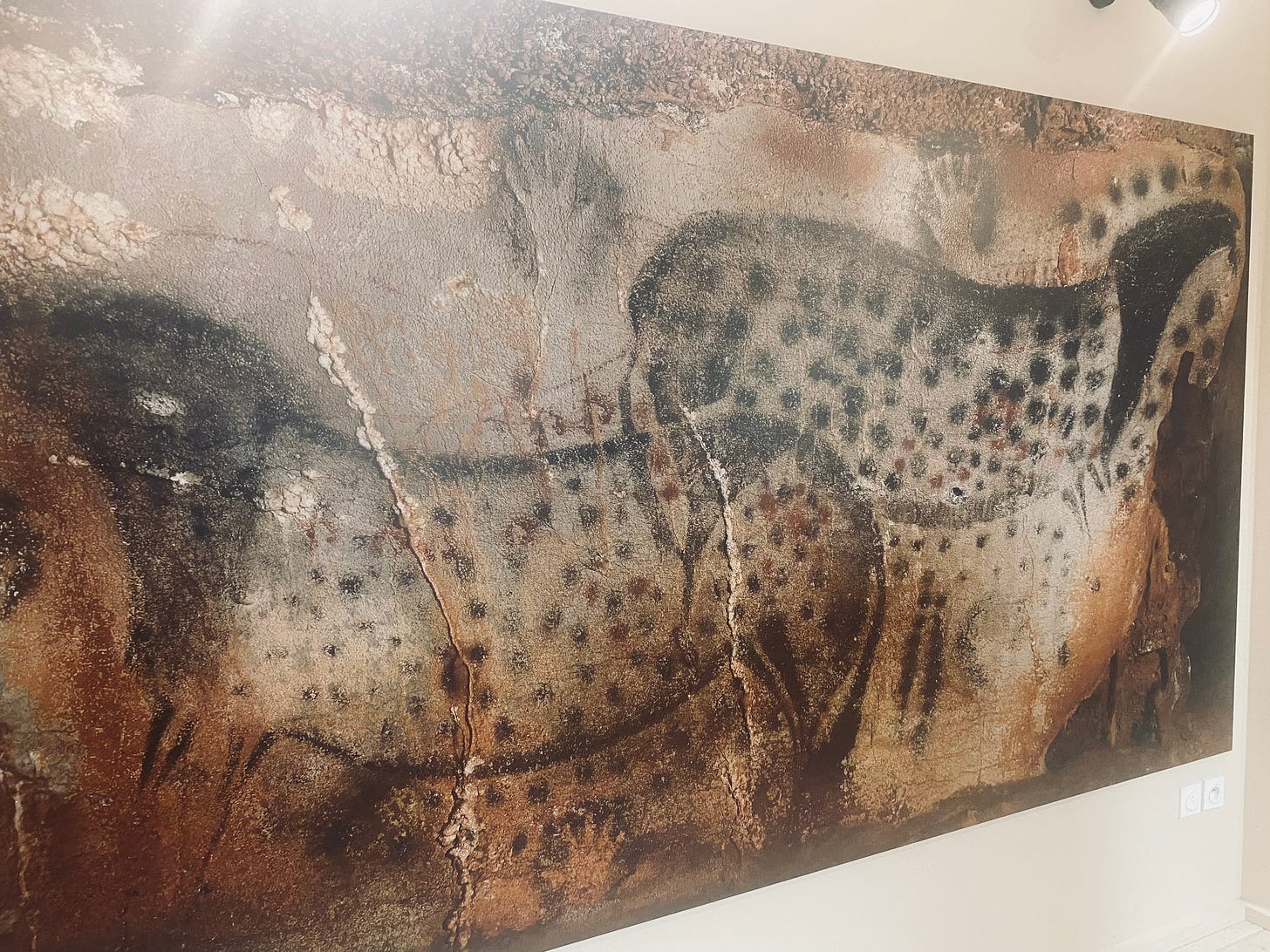

One of the things that I found myself thinking about, as I was visiting various caves in the Dordogne region in early July, is how much the field of archaeology must have changed the culture of that region as the science developed. The art in Chauvet Cave is thought to be the oldest of the Paleolithic cave galleries, with some images dated at around 27,000 years old. But it was also one of the most recently discovered; it was only unearthed in 1994. Other caves, like Lascaux and Pech Merle (which features one of my favorite frescoes: the spotted horses) were both discovered by local kids, earlier in the 20th century. The kids who discovered the art in Pech Merle were actually deputized by their local priest—Father Lemozi—to go out and look for Paleolithic art. He doubled as a prehistorian, and apparently gave his parishioners explicit instructions about what to do if they found any art (including what to leave in place, and never touch). Searching for caves must have become something like a local adventure game.

At least one of these Paleolithic caves, the grotto at Rouffignac, has been regularly visited over the course of its history. There are markings on the wall that clearly date back to early modernity. So we know that people were entering these caves, and observing the art, hundreds of years ago. But this was also before the invention of pre-history. Early modern French people, who explored the Rouffignac cave, must have known that these images had been left behind long ago. But it’s unlikely they hypothesized that these images came from something like the “dawn of human life on Earth.” And there wouldn’t have been priests encouraging people to place the images in this kind of historical context. A new way of thinking, speaking about, and framing history would need to develop and evolve before this could happen.

Perhaps this is why a cave like Rouffignac was able to remain intact, despite the fact that it did receive periodic human visitors. It wasn’t a pilgrimage site. The art on those walls had not yet, in early modernity, come to be understood as sacred relics of the the earliest human history. The caves at Lascaux (and Chauvet) were very different. These caves were discovered after the birth of prehistory. They immediately became pilgrimage sites for Paleolithic tourists who wanted to experience something human that was more ancient than the idea of time itself.

By the 1940s, when the caves at Lascaux were uncovered, Paleolithic tourism had already been established in the Dordogne region of France. This wasn’t the only cave that people could visit, but it was one of the most fantastic. Its galleries were more copious and its images were more colorful than other caves in the region. Visits to Lascaux boomed after World War II, when it was opened to the public. They brought their breath, their sweat, and the oils on their fingers with them. In less than twenty years, there was a rapid shift in the cave environment as the temperature changed. Moisture and fungi entered, along with these human visitors. The paintings began to fade. In 1963, the decision was made to seal Lascaux off to these human visitors.

Twenty years later, in 1983, Lascaux II—the first replica of the cave paintings—was built. This replica had been in the works since 1970, but it only featured a recreation of the two largest galleries. In 2016, the French government opened the new and improved Lascaux IV (Lascaux III was a traveling gallery). They’d spent more than 60 million euros to build it, and they’d made ample use of digital technology to create it. Not only does the replica feature a full recreation of all the galleries that have been sealed off in the cave, but it also features a whole room full of virtual encounters with the cave art. Some have argued that it’s better than the original.

Tourism and Authenticity

As I was planning my trip to France, to do research for my new project on underworlds, I actually questioned whether it would be worth my time to visit Lascaux. I’d been reading Robert MacFarlane’s Underland, which is a travel narrative into all kinds underworld spaces. MacFarlane decides to visit some ancient cave art, but rather than visit a place in the Dordogne region—which is crawling with tourists—he chooses to go far off the beaten path. He visits the remote decorated sea caves off the coast of Norway. More than half of his chapter is about the arduous journey he took, to get there in the first place.

Reading his account made me feel as if I should do be doing something similar. It seemed to me that I owed people something more authentic than what your average Paleolithic tourist could access. Why would I, a researcher, visit a place that had already been seen and witnessed by so many hundreds of thousands of people? Isn’t the whole point of a new project to challenge people to see things in new ways? To take them, through my writing, where they’ve never been?

It slowly dawned on me that this was absurd. I am the mother of a small child. I can’t take months off of my life to traipse into the far reaches of the earth. I have neither the time nor the money to do that kind of work. I began to realize that it was going to be difficult enough to find the time and money to do the same old sort of Paleolithic tourism that everyone else who made this sort of pilgrimage was doing. Not only would I have to get all the way to France, but I was going to have rent a car and drive through country highways to get there! The best I would be able to do was to travel the same well-worn paths that have been carved out by the hundreds of thousands of other people who’d been motivated to somehow come into contact with these sacred relics from deep time.

Underland, which I loved and appreciated, belongs to a genre of adventure literature that I will never write. My book project on the underworld was destined to be something completely different. I’m a scholar of religion: walking the beaten path that thousands of pilgrims had already walked made perfect sense for me. I began to realize that I wasn’t actually interested in trying to get off the beaten path, or to discover something presumably more “authentic” than the same old thing that every tourist encounters. Rather, I was in it precisely for the mediated experience. I wanted to see how it was that the Paleolithic world was being produced and curated for a hungry tourist like me—for a modern consumer of deep time.

Sacred Relics from Deep Time

There’s a case to be made that the 17,000 year old Paleolithic art of the Lascaux cave is merely a sub-phenomenon of deep time. The caves, themselves, are marks of deep time but the art that’s on them is modern, in comparison. I’m going to refer to the cave art, here, as if it’s part of deep time. Because I think that part of the appeal of witnessing this Paleolithic art, in the flesh, is that it makes us feel as if our human history is part of something much bigger than the historical timelines that are familiar to most of us. It feeds the sense that we are part of something in deep time—something that we still struggle to understand, and relate to. It feeds the sense that we, as humans, are part of something much more than human.

Caves like the one at Lascaux are relics of modern science, more than they are relics of something that sounds religious, like “sacred history.” And yet there is undeniably something sacred or holy, in these cave spaces, for many of the people who visit them. Almost every tour that I went on, into these underworld galleries, included some sort of oblique reference to this sacred dimension. Some of the guides asked us not to take photographs, not because they wanted to ensure that you have to visit the caves in person and pay the admission fees in order to really get a look at them. But, instead, because they are considered “too sacred” to be captured on our profane personal cameras. When we entered the replica, at Lascaux IV, we were all asked to observe a moment of silence, in recognition of the sacred experience we were about to encounter. So, clearly, part of the synthetic cave experience included a mediated recognition that we were doing something “holy.” Despite the fact that I am a scholar with a sharply honed sense of skepticism about any references to holiness, it felt kind of right to me.

There were aspects of the experience that felt more decidedly “profane.” Right before we entered the replica, we were ushered into a small room where a video with CGI imagery tried to recreate the look and feel of what the Paleolithic environment around the cave would have been like. We watched long extinct animals chase and hunt one another, on the screen, as the seasons rapidly changed from summer to winter. I got the point, but it felt a little gimmicky. And although the crowds were a constant cue to me that I was doing something Very Important, the struggle to see and hear and breathe through a crowd did minimize the holy feeling somehow.

But even in that cave replica, I felt like I was getting close to something very powerful. I don’t know that it felt “religious”. I am so skeptical about how that term is used. I find it both meaningless and too charged with meaning. But I did find myself thinking, over and over again, that so many things we think of as religious seem to be derivative of what I was experiencing, even in this cave replica. I had the feeling, for instance, that the shape and high ceilings of cathedrals were imitations of the inner recesses of these caves. This felt much more true, of course, in a real and colossal cave like Pech Merle. But it still felt true in my synthetic cave experience. The caves felt like a space that could have given birth to the church as such, or even to the gods.

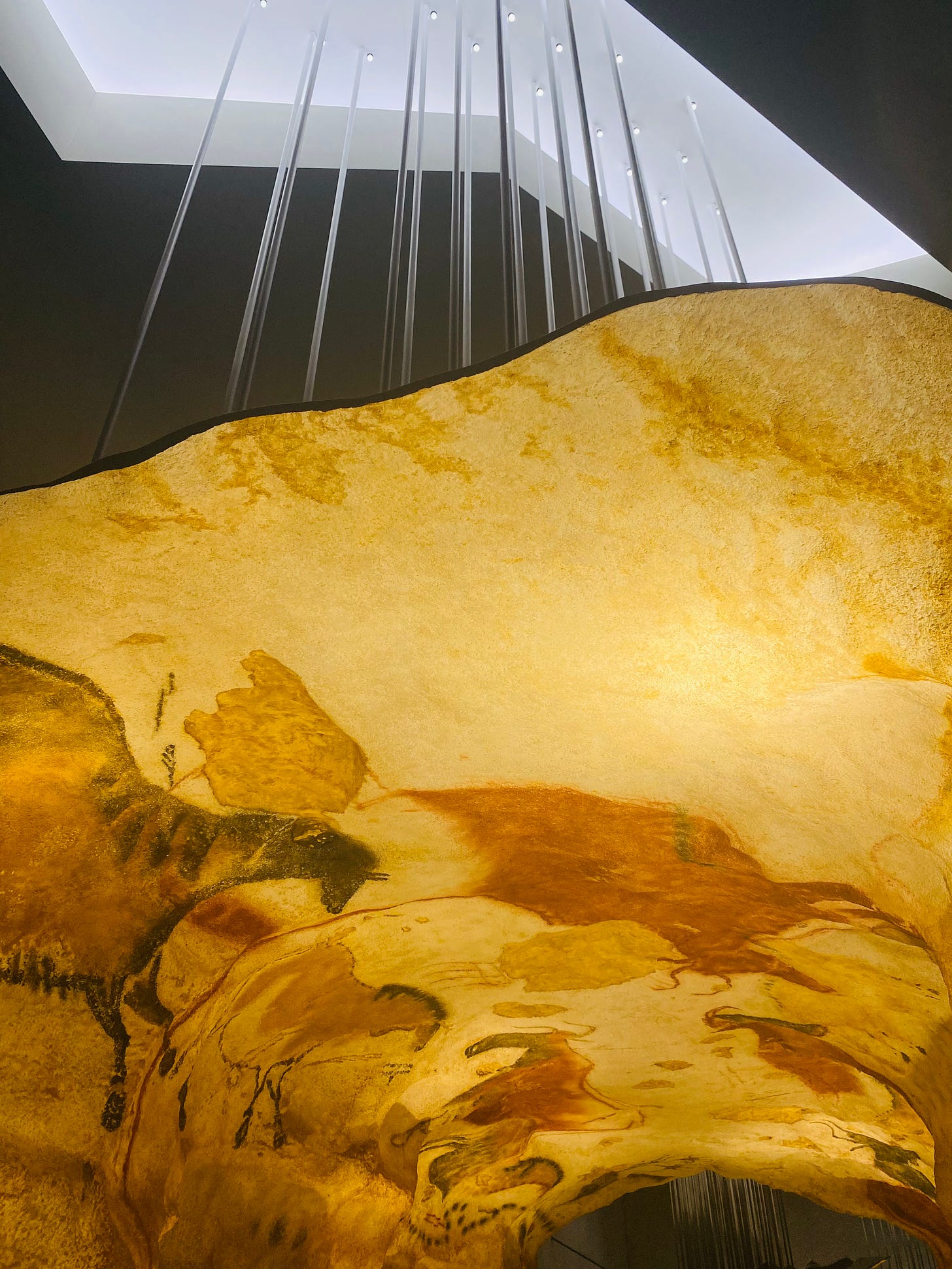

When we’d completed our tour through the immaculately duplicated caves, whose detailed recreation had been enabled by all manner of digital technologies, we were spit out in a large “workshop” space, where we could get a glimpse into the creation of the cave replicas. Intenstinal looking cave rooves were hung from the ceiling of the room. We were handed little tablets that acted as our tour guides through the room. And we could stand there and watch as little laser lights drew images on the fake cave walls, giving us a sense of what it might have looked like to watch these sketches appear in real time. It was very clear to me that I was in a hyper-curated space. But it still felt a bit magical, to watch these sketches emerge in bright lights. It was a great show.

The lights added to what felt, ultimately, like a kind of meditation. I was wrapped up in a sense of awe. It’s not that I had the feeling that I was close to the real thing. I knew that wasn’t true. I still felt quite far from the real thing (though I was as close as most people will ever get). Instead, I just found myself in a general state of shock that these caves exist, that people had been drawing on them tens of thousands of years ago, that the images had somehow been preserved and recovered, and that the French government had spent more than 60 million euros to replicate these galleries. What an investment!

In my synthetic cave experience, I had the distinct feeling that something powerful was being mediated for me. I don’t think I could name that power. It has something to do with humans, something to do with art, something to do with nature and the more than human, and something to do with time. But I know that I felt myself to be in the presence of something so powerful I would concede to describe it as sacred.

The power of relics has always been a mediating power. A relic feels powerful, as you come into contact with it. The finger bones of a dead saint probably felt sacred and powerful, to medieval pilgrims, not because they were fooling themselves into believing that they’d met a real saint. Instead, they just found themselves to be somehow—strangely, maybe even a bit magically—in the presence of some object that was tapped into something incredibly powerful. A sacred relic, from a deeper form of time.