LAST WEEK I presented at the annual meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association (ACLA). This was the second year in a row that I attended the ACLA, which I’d heard from numerous colleagues has a pretty rewarding seminar model. Instead of attending random sessions, you gather with the same group of people for sustained conversation on a central topic.

I’ve really enjoyed both seminars. Last year I was invited to take part in a seminar on the arboreal humanities, organized by Richard Grusin and others. This year, Alex Sorenson invited me to join a seminar on ecology, ecstasy, and mysticism. I appreciated the conversation with Alex, as well as scholars like Kate Rigby, Thomas Carlson, and Roger Gottlieb. And I liked the essay I wrote for the seminar enough that I wanted to share it with you.

Over the past year or so, I’ve been singing a lot more than I used to. I felt compelled to, for some reason that still don’t quite understand. I’m not a musician (though I have picked up the guitar again, to have something to sing along with). Because I overthink everything I do, this means that I’ve also been thinking about singing, and voices, a lot more. As I was writing this essay, I was under the impression that it was the first thing I’d ever written on acoustic ecology… until I remembered this essay I published in 2022 on silence (or hearing nothing).

I wrote this particular essay because I wanted to think about why it is that having a voice, and using it, makes me feel like I’m growing roots that I’ve forgotten to water for a long time. And I’m asking the medieval German abbess (and lover of green things) Hildegard of Bingen to help me think about why that is.

Incidentally, the essay I wrote for last year’s ACLA was just published in a cool issue of the journal SubStance, which is all about trees. If you like trees, it’s an issue worth checking out!

NOT LONG AGO, on a walk in the woods near my house, I was suddenly struck by a chorus of turkey tail mushrooms that had emerged from a decaying log. Every single visible mushroom was curling upward, perhaps to offer their spores generously to the passing breeze. But there was something about their shape and form that struck me as reverential. It looked to me as if they were casting their senses up toward the heavens, as if they were making some gesture of praise for what stirred above them, as if they could have been singing out. I felt like I could hear their little voices—layered, and multi-tonal.

It made me want to hear a chant—some sort of sacred sound. And I had little buds in my ears, just waiting to flower forth with some sort of sound on-demand. I cast about through the seemingly infinite set of options that were available to me with the touch of a finger and ended up playing a performance of medieval chants, composed by Hildegard of Bingen. The sound ran through me, raising the hairs on my arms a bit. I found myself, as I listened, drawn to all sort of strange patterns in things, as if my gaze were being stretched and contracted in unfamiliar new ways. It felt to me as if everything, from the turkey tails to the bark of trees, to the little hairs on my arms, was dancing together in a very slow temporality. I didn’t know the music: it was unfamiliar to me. But I felt a sound emerging somewhere in my belly. It ran up through my throat and passed from my mouth as a little hum, without any real intention. It flowed into the forest around me, as if it had always been there.

MUSIC, ESPECIALLY SINGING and vocalization, has always played a critical role in the environmental movement. From songs like Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi”, John Prine’s “Paradise”, or Jean Ritchie’s “Black Waters” to the music composed with the first recorded communication between whales, there seems to be a dimension of environmental awareness that emerges clearly in song. It makes a certain kind of immediate sense, at least on an intuitive level. While music is something that we describe as cultural, it is also one of the most animal, and even vegetal, things that we do.

Where did we get our strange range of sounds, and our rhythmic patterns, if not for our conversations with the songs of birds or the percussive rustle of leaves? Immersing ourselves in music can feel like retreat into an environment. Not entirely unlike the way that we immerse ourselves in a forest, immersion in music can invoke powers within us that run through the biological form of our bodies, but also seems to tap into forces far beyond them. The source of our music is within our bodies—within our nature-bound forms. But our bodies are pulling these sounds from, and weaving them back into, the larger, complex, more than human world all around us.

The vibrations of sound that we sing or chant have been central to acts of worship or praise in religious rituals and traditions. Some of these traditions (especially indigenous ones) acknowledge the way that our song weaves us back into the world around us. But religions with a civilizational spread and imperial roots tend not to lead with this connective practice.

Nevertheless, singing is still typically understood (even in these in religious contexts) as a tool for connecting with the more than human world—at least in its divine or spirited registers. Song is a notorious tool for elevation—a way to lift one’s spirit a little higher, and closer to the heavens. The unifying power of song, in a worship ritual or setting, draws those who sing outside of themselves and weaves them into something both is, and is not, of them. It’s within their bodies, but also bigger than their bodies. Song often uses language, but also undoes it. It’s a boundary object that inhabits the things we hold most sacred while also rupturing them, to access the realms that exceed our human sensibility and perception.

Our songs, whether we acknowledge this or not, are part of our human cultural life that taps—as if by a force of nature—into more than human dimensions. If we look carefully, it becomes quite obvious in song itself that the animal, vegetal, and divine dimensions of more than human worlds bleed together in musical sound. Song communicates with these worlds, expresses these worlds, and so binds us to these worlds.

I think that Hildegard of Bingen is a figure whose life, music, and words illustrates this quite well. When we sing—I want to hypothesize, with Hildegard—we activate something in the materiality of our bodies and voices that we might also describe as the earth feeling and sensing herself. In this way, perhaps, we can think of singing as both ecstatic and ecological or at least it has that potential: it’s an ecstatic emanation with an ecological application. Perhaps, as I think Hildegard can prompt us to contemplate, we can sing down something like a paradise in the textures of our songs.

HILDEGARD WAS A German abbess, born in 1098. She passed in 1179, but her legacy has been long. As a religious figure she’s experienced something of a revival in recent decades, as scholars have been digging through history in search of the buried or muted spiritual wisdom of women. She’s well known these days for her mystical visions described in texts such as her Scivias. But she is also known as a composer—though she never wrote any music that would be recognized as a formal composition in the way that we tend to use the term today. Her deep interests in botany have also made her intriguing to those who are looking for ecotheological models in the deep past of Christianity. She is a figure whose life and work blends together music, mysticism, and ecology.

Her writing isn’t filled with copious commentaries on paradise. But one that I find compelling is seeded in Scivias. Paradise, Hildegard suggests here, is paradigmatically “the place of delight”. This fantastic spacetime of delight “blooms with the freshness of flowers and grass and the charms of spices,” it is “full of fine odors and dowered with the joy of blessed souls.” There is something about paradise that renews and restores, it gives “invigorating moisture to the dry ground” and it “supplies strong force to the earth” just as “the soul gives strength to the body.”

What I find interesting about this notion of paradise is just how close it seems to be to the earth itself. While there does seem to be a sense in which paradise is not of the earth (it’s a spacetime of delight, somehow beyond this world of suffering and sin), Hildegard also suggests that paradise is not a spacetime entirely disconnected from the earth, either.

The content of paradise are things of this world—flowers, grasses, and spices. What we might look toward or hope for in a paradise are elements of creation that already look familiar to us. But, more than that, Hildegard also suggests that one key function of paradise is to perform a kind of healing work on the earth. Paradise invigorates the driest places on earth with moisture—perhaps we could think of it as a kind of holy water. But paradise isn’t simply wet. It’s also a work of spirit.

Paradise seems to be, in Hildegard’s description, something like the soul of the earth. It is, we might imagine, what enlivens the earth and lifts it up: what keeps the earth itself from being mere matter. And what keeps it from shriveling up. Paradise, perhaps, is the spiritual core of the earth—its secret heart, or interior castle.

PLANT PHILOSOPHER Michael Marder argues that Hildegard’s ecotheology orients itself around the notion of viriditas. The term translates from the Latin as, literally, “the greening green.” But Marder glosses the term as, instead, “a self-refreshing vegetal power of creation ingrained in all finite beings.” Viriditas, he argues, is a word for freshness.

While Hildegard was certainly interested in botany, viriditas or freshness was not simply a description of plant life. Rather, it was a description of the vegetal powers in life—powers which were divine in their source and nature. Marder likens the power of freshness to a kind of “earthward movement” of divine incarnation. Freshness, then, is a fundamentally theological concept which plays out in divine registers and becomes, in essence, a work of divine power as it functions in vegetal ways.

Marder also argues that, for Hildegard, “the drama of sin and salvation is played out between the environmental poles of the forest and the desert.” The revitalizing freshness of viriditas contrasts with ariditas—a deadly force of scorching heat. Viriditas allows for a kind of self-regeneration and facilitates a more capacious relationship between body and soul, while ariditas hardens the divisions and “exhausts life itself.” We could say that ariditas or dryness has a counter-theological function, though I’m not sure it would be right to suggest that it can be likened in a simple way to evil.

We can see these powers—viriditas and ariditas—at work in Hildegard’s description of paradise that I’ve already referenced, I think. One of the functions of paradise, she suggests, is to regenerate the earth when it has become dry—when the life of earth has been exhausted. This is the spiritual regeneration that paradise facilitates: the ensoulment of something paradisiacal within the body of the earth.

Perhaps we could say that paradise, as Hildegard describes it for us, is the making-present of viriditas or freshness. It is what happens, in space and time, when viriditas makes itself apparent in and on the body of the earth. Paradise is the source of the planet’s freshness.

Hildegard doesn’t suggest, in the passages I’ve cited, that paradise is a song, or that paradise is present in the songs that we sing. She doesn’t explicitly state that we help to restore the freshness of the earth when we sing. But I don’t think it’s entirely unreasonable to imagine that she saw things this way.

Marder emphasizes that freshness, for Hildegard, had “tonalities and modulations.” The power of freshness was expressed, for Hildegard, through a “symphony of being” and was part of her broader sense of a general “sonority of being.” For this reason, Marder suggests, freshness describes a kind of “vegetal vitality” that also “furnishes a language for singing the world.” Freshness, we could say, sings. And the way that freshness becomes present in the world is, in part, through sound and sonority—it enters into the body of the earth through the symphonic powers of freshness, as movements of the soul.

It may not be a leap to imagine that this power of freshness might be at work in the sonorous rustle of leaves, as the wind works its way through them. Trees, and their leaves, are obviously vegetal and clearly part of the greening green that is freshness. But what about us? Are we agents of freshness as well? Are we capable of passing along the sonorous vegetal dimensions of freshness?

Marder suggests that we are—indeed, that freshness itself is a power of being that works in and across realms. Hildegard’s viriditas, he argues, is not simply or reductively a power within green things. It is, rather, “the energy of creation and re-creation.” Plants are visibly and obviously green. But humans, says Marder, nevertheless also possess “a dash of invisible greenness” not “as a substantive quality but as an activity of making-green, connected to the creative energy boiling in the Word.”

When we are overflowing with the regenerative powers of creation, we are filled with freshness. It may be the case that freshness is a bit “lopsided and perverted in us.” Perhaps especially to the extent that we are, or become, agents of ariditas (depriving the earth of its life and vitality), we lack the freshness that is so clear and apparent in the vegetal world. But we have the capacity for it. Perhaps it’s in song, or in our most sonorous or symphonic creative moments, that we possess the capacity for freshness.

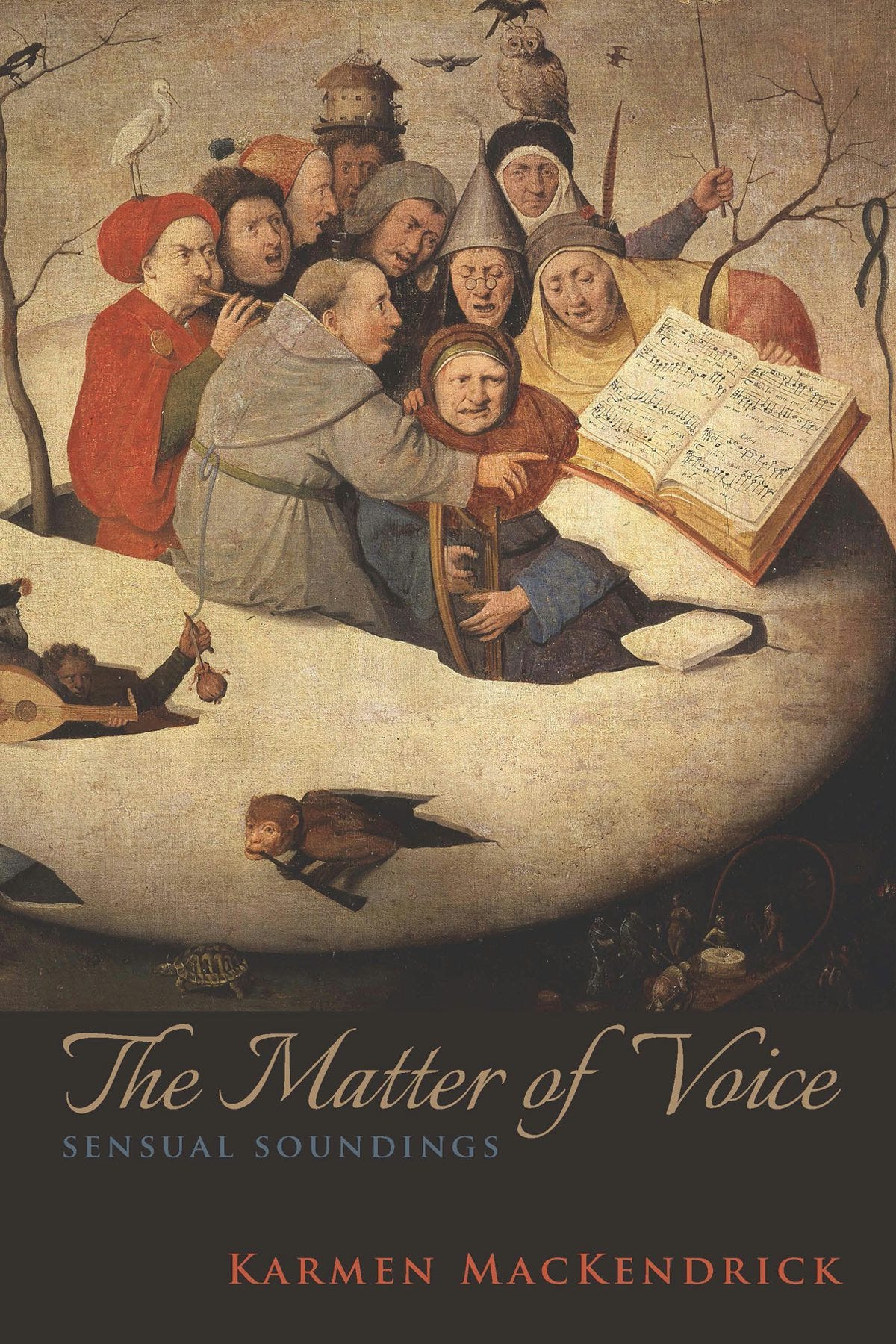

PHILOSOPHER KARMEN MACKENDRICK emphasizes that for Hildegard of Bingen, song—especially chants like the ones she designed to be performed in a formal, cyclical, and liturgical setting, was a form of worship. Hildegard considered the biblical fall from grace, or the loss of paradise, to also be the loss of song. But she also believed that we can bring it back, or at least make it present in a flicker of delight, through song. We can sing a divine freshness back into being, with our song.

The fall from grace, the fall into life, was also—Hildegard suggested—the loss of a song. In essence her argument is that, in paradise before the fall, Adam had an angelic voice—he had the capacity to sing with the voice of an angel. Here in the world, we speak and sing without that angelic voice. We’ve lost it—that is (among other things) our punishment. And yet, it’s through voice and song that we begin to reincorporate or invoke that holy sound once again. When we can sing in something that approximates the voice of an angel, it is as if we have restored a bit of paradise.

“The chorus of song is not itself celestial harmony” for Hildegard, as MacKendrick describes it. “But it comes as near as we can to giving that harmony [of paradise] a human voice.” In this sense, for Hildegard, music becomes both transformative and cosmically expansive. “For her, the whole world is made and remade by song.” Song restores the creation, and enlivens it.

There are other thinkers and music-makers who understand music as cosmological, or who understand the cosmos as fundamentally musical (sung into being, essentially). This isn’t unique to Hildegard, says MacKendrick. But Hildegard’s cosmology is “unusually musical,” MacKendrick notes, and it also has “an unusual measure of joy.” It is closer to paradise, or more in touch with the delight of paradise, than others perhaps.

Notably, MacKendrick (like Marder) clarifies that Hildegard’s sense of music is not limited to human song. We make music, and we sing songs, of course. And this is how we participate in the delight of creation. It’s how we offer a form of worship back to the creator. But music is something that belongs to the powers of creation, and it’s something we do that puts us in touch with—and helps us resonate with—more than human worlds.

Most of the songs that Hildegard composed are responsive, in their form. She composed many antiphons, which were designed to be sung back and forth between (for example) a single voice and a choir. Her nuns would sing call and response songs to one another, across the aisles of a church. MacKendrick emphasizes the extent to which this is not only relational, but also polyphonic like nature itself.

For Hildegard, MacKendrick writes, “humans are no more disconnectable form other organisms than from God, from other heavenly bodies, or from the earth. To pluck one string of the cosmos—the human body, the natural world, the art of music, the planets, the elements, the humors, the angels—is to set all of it vibrating.” And, in vibrating, “it sings.” Any one element of creation singing to itself, in its own form of song, has the power to resonate with the tones and vibrations of all other creatures. Maybe there’s something reminiscent of paradise, in this resonance.

PERHAPS BECAUSE VISIONS OF HEAVEN have, traditionally, been lined with so many clouds—and always draw our eyes upward—I think that I’ve always had the tendency to assume that visions of paradise also stand apart from the earth. This has been true for me, even as I’ve also always been aware of the fact that paradise is a garden.

Doctrinally, of course, in traditions like Christianity, the figure of paradise is a lost spacetime. Paradise is not for us: it’s something that we could have had, but for the force of sin. It’s something no longer available. It’s something that might someday be available again. But what makes paradise distinct is precisely the fact that it’s not this world of suffering. It is other to the world of corruption and sin that we inhabit. It’s the promise of something else: something other than this life we lead on earth.

And yet, I think, what Hildegard’s musical ecotheology suggests to us is that this may only be partially true. Indeed, I hear her suggesting that there are ways to bring paradise down to earth. And music, especially song, might be the primary delight that can help us do this.

I read Hildegard’s invocation of paradise as one that’s not severed from the earth or separated from it (not something that promises us a spacetime outside of, or beyond, this earth). Rather, her ideas make me wonder if perhaps—through song—we are able to feel the earth feeling herself. Perhaps we are able to feel the earth accessing her innermost self, her spiritual dimensions, those part of herself deep within herself (and within us, as earth bodies).

Perhaps, that is to say, our songs are also the sounds of the earth’s inner life. What if this innermost secret heart of the earth is also part of what we feel moving through us when we sing? Is this the song that invoked or provoked me (what made me want to sing) along with the cupped hands of the turkey tails in the woods? Was I feeling the feeling of the earth, sensing herself sonically and coming alive with the delightful feeling of her own powers of freshness, restoring what’s been shriveled, dried up, or exhausted? Was that sound—within me and yet somehow also not of me—that same freshness?

Honey, you're just too deep for me.

https://www.google.com/search?q=Here%27s+your+brain+on+music&oq=Here%27s+your+brain+on+music&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigATIHCAIQIRigATIHCAMQIRigATIHCAQQIRigATIHCAUQIRigATIHCAYQIRirAtIBCjE2Njk0ajBqMTWoAgiwAgHxBVZZsWNqPnz88QVWWbFjaj58_A&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:d9b380ff,vid:lyt8EmsJIBA,st:0

BTW, I'm kind of old school:

https://michaelsparks.substack.com/p/a-michael-from-mountains-guitar-centric