I own several decks of tarot cards, but I’ve only paid for a tarot card reading once. I was living in Brooklyn at the time and found myself wandering, late at night and a bit drunk, with a couple of friends in Williamsburg. We almost stumbled over an A-frame sign on the sidewalk advertising tarot card readings. The next thing I knew, we were taking turns sitting on the white leather sofa of a second-floor apartment, watching something on a big screen TV with a small but indifferent child as each of us had our turn at a reading in the other room. In my memory, I’m also smoking a cigarette. But don’t judge me, I may have invented that memory for dramatic effect.

I don’t recall how much we paid for the reading. I have no recollection of the cards she pulled, or the spread she used. The only thing I remember about the experience was the interesting feeling of being in a complete stranger’s living room, looking for some sort of insight into my life. I also remember the feeling of anticipation: when you know you’re about to share something you never get to talk about, and you feel like you might be on the verge of impulsively changing your mind about it.

I didn’t believe that this reader could predict the future, of course. That’s never something I’ve bought into. I don’t believe that a deck of cards dreamt into being by 19th and 20th century students of the occult have any objective power, in and of themselves. But, to be clear, I do think that there are unseen powers in and around the cards.

The Unseen Powers

I own multiple decks of tarot cards largely because the tarot is in broad circulation. I own other decks of cards that, in my opinion, are more beautiful and useful (like Krista Dragomer’s Gut Lights & Moon Shadow cards). There’s something incredibly pleasing about a beautiful piece of paper you can hold in your hand. But the standard Rider-Waite tarot deck isn’t especially lovely. Why do I still bother with it? In large part because millions of other people are reading and using these cards. In broad circulation, the symbols on the deck become a sort of shorthand. I take pleasure in recognizing when someone is adorned with the devil, the hermit, the empress, the two of swords (my own personal favorite) and imagining that I’ve opened a tiny window into someone else’s interior reality. So, one of the unseen powers of the cards is their efficient symbolic effect.

Because the deck is familiar, I know lots of people who like to spread it out, pull a card, and find something to talk about. Small talk is often boring. Even worse, many people have lost the skill for making it, since the pandemic changed everything. If you’re sitting around with a friend (or even an acquaintance) and you open up a deck of cards, it’s likely you will suddenly find yourself talking about childhood, dreams and ambitions, or recent forays into love and sex. So, another unseen power is that the cards can be a sharp knife to cut through bullshit and make life a little more interesting.

The cards also have the power to shape your attention. Few things are as captivating as the screen of our phones. But the cards are odd, sometimes even arresting. You can, of course, take pictures of them with your phone. And you can troll the internet, on your phone, looking for interpretations of them. But when someone offers you an interpretation of the card you’ve just drawn, it’s difficult not to be captured by the spell of their gesture at meaning making—even if just for a moment. The cards give other people the power to make meaning for you, or out of you. Even if they’re completely wrong, it’s often entertaining just to hear them out. And because you might be invested in what they have to say, it’s easy to lavish them with attention. Perhaps nothing is more of a gift, in this economy, than our attention. Anything that challenges you to lavish your attention on a real, living, human person has power.

When you play with a deck, on your own, the cards can also offer you a number of different possible conversations with yourself. Perhaps it’s because I was an only child (who became a writer), but I’m a solitary creature who happens to think of conversations with myself as social. The simple act of stopping to think about my life, what I’m doing and why I’m doing it, is a luxury I don’t often have. Drawing a card can be a contemplative discipline, or ritual, that gives you social access to whatever inner voices it’s usually more convenient to silence. So, the cards have the power to redirect you toward the less visible, unseen (sometimes buried) dimensions inside yourself.

The Death Card

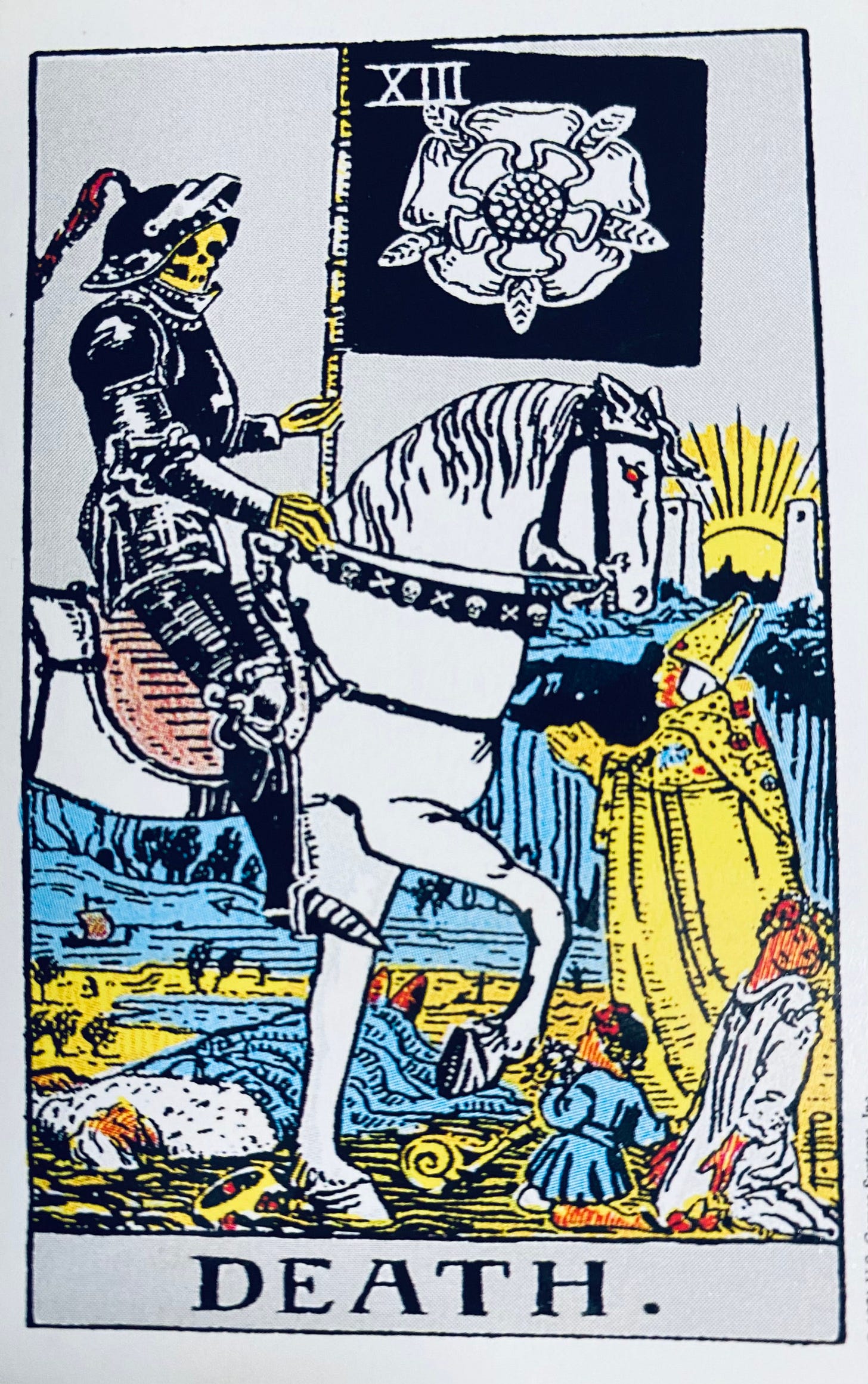

There are several cards in the familiar Rider-Waite tarot deck that are uniquely morbid and seem designed to terrify. Death, the tower, and the nine or ten of swords are probably the worst. If you’ve never seen an actual tarot deck, you’ve still probably seen these cards used as a kind of shorthand on TV, or in the movies. This scene, from “Killing Eve” efficiently uses both death and the tower to signal past trauma and future doom.

Despite this, most people who have invested time in learning to read the tarot will caution people to be unafraid of the death card, in particular. What the card means, readers often assure us, is something more symbolic. Pay no attention to the dead body on the ground, or the skeleton in a suit of armor, in other words. The card is not about physical death but instead a kind of spiritual or figurative death. The card serves as a symbol of change and transformation—one that draws your attention to a loss you might have experienced, or something you need to shed.

The Philosopher’s Tarot (a fun reinterpretation of the Rider-Waite deck that anyone who enjoys both philosophy and tarot will love) surfaces this reading of the death card. “We live in a world in which death is often obscured in an effort to project the illusion of an interminable continuity of all that exists,” the guidebook observes. The philosopher who occupies the space of death, in this deck of cards, is Georges Bataille whose book Inner Experience famously critiques the denial of death as a dimension of fascism. “How could we become become intense enough,” the guidebook asks us, “to dip our toe just far enough over the liminal edge of the known where death itself is said to reside?” I love this question. I probably ask myself some version of it every day (in case you’ve ever wondered why I’m so intense).

There is, in other words, a standard reading of the death card among those who are familiar with the tarot. It’s not a card of horror and doom, but instead a card of change and transformation. I’m often driven in iconoclastic directions when it comes to meaning making, however, for better and for worse. So, I’ve come to read the card a little differently. I don’t think that the symbolism of the card is just a figurative reading of death. I think it has something to say about actual physical death, and how it’s often understood.

How I Read the Death Card

The suit of armor, on the death card, is not incidental. Neither is the battlefield with a dead body. This is a scene of war. The colors that dominate the background are blue, gray, and black. The environment is muted. There’s almost nothing life-giving about it. Death (we can assume) is the skeleton in armor, riding on a white horse with unsettling red eyes. This is scene of war, and it appears that death has won.

Death, the great equalizer, has laid power itself low. Near the collapsed figure on the ground we see a crown and scepter. The king is (presumably) dead. The other face of power—a priest—appears to either be begging death for mercy, or asking God for salvation from this world of death.

The scene that’s been sketched out is the one set for us by the political theology of death that I critique in my book, Sister Death. Life and death are at war. Death is the enemy, and Christianity proclaims the triumph of life and all things good. This card seems to take this Christian metaphysics for granted, but reverses it. Instead, it’s death that triumphs, who even makes the priest beg for mercy. The Rider-Waite deck, which intentionally made use of occult symbolism, has often been associated with what the church condemns (such as heretics). For this reason, an intentionally irreverent transformation like this would be predictable.

But it’s difficult to miss the fact that the most dominant element in the image is the black flag, emblazoned with a white rose. This is apparently the white rose of York. It’s a symbol that would have been a heraldic badge in the Middle Ages, but would have accrued different meanings by the 19th century when this card was created. By this time the rose would have apparently had liturgical associations. It could have been an emblem of life, purity, or innocence. It’s interesting to note that this is the banner that death raises: a flag of innocence, purity, or life. And notice that the children in front of death’s white horse are untouched. Death isn’t even looking at them. And the sun rises, hopefully, on the horizon.

If death serves a symbolic function here, perhaps that function is to raise a critical question. Is death the figure of ultimate evil? Is death at war with all things good, and pure, and innocent? Or is death itself innocent of the charges against it? This can raise questions, too, about what we’ve chosen to demonize or think of as evil. What forces have we set against one another, perhaps to our own detriment? What battles have we convinced ourselves we are fighting in? And is this a war we really want to fight?

Perhaps this is less an exercise in becoming intense than it is an exercise in de-intensification. And yet, there’s a kind of intensity that we encounter only when we walk into a space we used to believe was one of conflict. Where we once expected to find something to resist and something else to ally with, we instead find ourselves caught up in the charged counterpoints of opposition; living in the ambiguity of a paradox, feeling pulled in two directions at once. It’s not an easy place to be. But it can be exciting.