Underworld spaces aren’t, typically, for us. For humans. They aren’t typically spaces where we can live, and grow, and thrive. It’s difficult for us to see, or even breathe, under the ground. There are plenty of species that thrive underground. We don’t tend to be among them. The great exception, perhaps, is our dead. Underworlds—at least mythologically—have been worlds for our dead. While many today will most immediately associate the underworld with hell, it hasn’t always been understood as a space of pure torture. The Ancient Greek underworld, famously, was a more neutral and ambivalent zone. Not a cheery or pleasant place to be, perhaps, but not necessarily a site of eternal damnation and torture, either.

Or was this only true for the men? Was the experience of an underworld space like Hades different for women?

“As far back as the classical katabases,” argues Robert Macfarlane, “it is often men who descend heroically to the underworld to retrieve women who have been trapped, taken, or lost.” We see this in the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, for instance. It’s the men who have the privilege of just dipping their toes into the underworld and resurfacing. It’s the men who must be relied on to save women from an uncertain underworld fate. And then, of course, there are figures like Persephone who were taken to the underworld violently and (except for an annual reprieve) can never go home again. “Mythologically, the underland is often a place where women are silenced or pay brutal prices for the mistakes of men,” Macfarlane reflects.

Perhaps the underworld has always been a hellscape, for women: a space of violent suffocation. But what if it’s been something else? These ancient myths, after all, have been filtered to us through the voices of men like Homer. We often read the underworld with a gender bias. What would underworlds look like, or feel like, if women were our guides? How might we see them differently?

Adventures in Underland

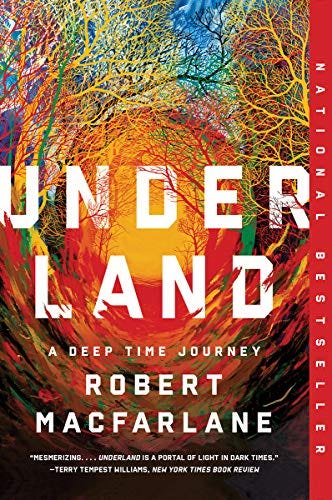

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you know that I’m currently working on a new book project, on underworlds. To me, it feels like a radical departure from my recently published book on death. But from the comments I’ve been getting, I suppose that it also looks like a logical next step. There’s some thematic overlap. I recently read a book for research—Robert Macfarlane’s Underland—that I actually tried to read several years ago, but struggled to get into. This time, something was different. I was so entranced by the book, in fact, that it made me wonder why I should even bother writing my own.

This is, I’ve learned, one of the necessary steps in a long writing project: you find a book on your chosen topic that’s so good, it throws your entire project into question. But this also ends up becoming a key moment of transition, as you begin to realize that this book is actually giving you permission to write about something other—something better—than what you’d originally intended to say.

Macfarlane’s Underland is a masterful survey and study of underworlds of all sorts—real and imagined, geological and historical. He doesn’t call them underworlds, of course, but instead refers to them (in less mythical and more earthy terms) as underlands. The book apparently took him more than a decade to write, and I can understand why. It’s both poetic and encyclopedic. After I’d had the chance to digest it, I felt a sense of great relief to be unburdened of any real need to be broad in scope, or comprehensive, when it comes to my own underworld project.

Once I’d digested the book, I also felt a series of new and insistent questions bubbling to the surface. One of the things that has been gnawing at me is Macfarlane’s musings on the women of the underworld. Is this all that the underworld has been for centuries of women? Do we lack other stories of women’s adventures the the underworld? Do they simply not exist? Or have they been muted, or forgotten? Do we simply need different lenses to read, or decode them?

One of the things that’s quite distinct about Macfarlane’s Underland is that it’s a book that repeats and performs some of the heroic tropes that we see in men’s ancient katabatic (of the underworld) journeys and adventures. Macfarlane writes about the environment (including the destruction and exploitation of it). The trope of the adventurer who investigates the furthest reaches of the earth, in order to inform the rest of us about what he found there (and why the rest of us should leave it alone) is pretty common in environmental literature.

These tropes are what give Macfarlane’s book its voice and texture. He’s not just giving us a cultural history of underworld spaces (although he certainly does some of this). He’s also telling us the stories of the faraway underworld spaces he managed to adventure to, and explore, in his research. He tells us about how difficult it was to get there, what these spaces look and feel like, and who he found there. If I’m being completely honest, I will admit that these were also the least interesting parts of the book, to me. They were simply the parts I cared least about, the parts that bored me the most. They were the parts I skimmed through. I was much more interested in the cultural histories of underworld spaces—the bigger stories about how people have made meaning out of underworlds and underlands.

Perhaps the issue is that I had trouble getting excited about being in his position: imagining myself descending (willingly) into dark and dangerous caves in remote places where people rarely venture. My life has become incredibly settled, and domestic. It’s the fate of many women across the course of history, we know. They become mothers, they settle in a nest. It’s a familiar story that’s often treated as a genre of tragedy, but I don’t experience it that way. I just think differently than I used to about what it means to be an explorer, and what I want to explore. There was a time in my life when I was obsessed with remote mountain peaks, and I chased the feeling of being as alone as possible on one of them. That’s just not where I feel my spirits drawing me, anymore. It’s not what concerns me.

I suppose all I’m trying to say is that I’m feeling drawn to explore underworlds by different means and methods. I’m drawn to think about adventures in the underland quite differently. I’m not interested in getting myself to the remotest possible underworld space and reporting back, from there. I’m looking for another sort of information about the underworlds.

The Belly of the Earth

Interestingly, on my most recent journey I found some of these stories beginning to gather around me, as if by some sort of magnetic force. Last week I was in New York, for an event at Risen Division - in Red Hook, Brooklyn - that we called Soils of Sisterhood. It was a celebration of Sister Death, including the art in the book by Krista Dragomer. It ended up being a wonderful opportunity for us to celebrate the collaborative work we’ve been doing for more than a decade. I was grateful for the opportunity to see old friends, and to meet new ones. I end Sister Death with a reflection on burial rituals that - in some way or form - help us to decompose, to become dirt. We wanted to celebrate the rhizomatic and fungal connections that spread, in ways we can only just barely conceive of, in the soils of the earth. So the event was, in its own way, already underworld-oriented, after a fashion.

But I was struck by how many little underworld visions I kept discovering, while I was there. I want to tell you about all of them, but I don’t think that either you or I have the time or space.

One of the most striking, and exciting, was in the Wangechi Mutu show that Krista and I went to see at the New Museum. The exhibition is phenomenal. If you’re in New York before June it’s definitely worth seeing. The museum has given over its entire entire gallery space to her work. The lower floors of the museum house her earlier work, and the upper floors her most recent. Krista and I have been mutually inspired (in different ways) by Mutu’s work for many years, so we began on the lower floors with a feeling of nostalgia. We’d seen much of this work exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum back in 2014, and it felt a bit like walking back in time. I spent a long time looking at one of my favorite pieces, “Riding Death in my Sleep” (2002) and wondering how much the work in my own book had been inspired by it.

Mutu’s work has always illuminated the porous boundaries between what are often considered fixed lines in our understanding of race, gender, and species. Many of her most famous images are speculative visions of bodies that feel marked in clear ways by the racism, misogyny, and exploitation of coloniality and capitalism. There is an unmistakable feeling of violence in these images. But her figures also radiate an incredible beauty and power. The figures feel deeply ambivalent: both captured yet also irrepressibly fugitive. And yet there’s always this sense that they are mediating some sort of information to you through a set of structures (racializing, sexualizing, speciating) that are fundamentally hostile. You feel your capture, within these structures, as well.

The figures in Subterranea are similar, in many ways, to her earlier figures. The porous boundaries between race, gender, and species are still there. But they are also very different. The underworld environment that surrounds the figures looks, at first glance, a bit horrifying. But when you step closer what looks bloody or skeletal or violent begins to look, instead, like a gorgeous adornment. The faces of the women, in the images, are powerful, ecstatic, or even at peace. There’s something that I can only describe as a kind of spiritual power that Mutu seems to be offering, in the images.

I took a number of photos, of the images, but I won’t post them here because it would violate copyrights. You can, however, see a host of photos in the exhibition (including some of the Subterranea images) here. I’m also posting the cover from a new Phaidon book on Mutu, below, which features a Subterranea image.

In all of the images there’s a repeating structure that is also on display in Mutu’s short film “My Cave Call” (2021). The film begins with a pastoral scene, with cows, and moves to a scene with the artist falling asleep while reading under a tree (clearly an allusion to Alice in Wonderland). Butterflies gather around her body, as she sleeps. Suddenly the figure is in an underground cave, just barely touched by the light from an opening. She, like all of the figures in the Subterranea series, has a set of gigantic arms with no hands. They look like horns, or wings, or even fins. In the film these arms are emitting smoke, as if they were incense burners in a sanctuary.

There’s the sense of a kind of invisible violence, in the film and in the Subterranea series. You don’t get the sense, for instance, that the woman who finds herself in the cave is there by choice. She seems to have fallen, against her will. It’s not easy to discern whether she finds herself in solitude, or if she’s been enclosed. Nevertheless this figure illuminates a kind of power. Perhaps she’s making some kind of magic that comes from the belly of the earth (a phrase that pops up on screen, in the film). There’s something almost hopeful, or maybe just magical, that rises like the smoke.

When I was in New York I was speaking with someone about the new Bijörk song “Ovule”. I was mentioning, more specifically, her line “hope is a muscle that allows us to connect.” When I came home, I found the video, so that I could send it in a message, and I was surprised to discover that it takes place in an environment that is, clearly, quite subterranean. The fungal connections in this space show up like some sort of manifestation of that muscular connection that Bijörk invokes. It seemed to fit with my growing sense that I was receiving a different set of transmissions about underworld spaces. They’ve left me with the lingering sense that the stories I want to tell are part of an emerging set: tales about the powers still to be found in the submerged spaces, or the spaces we’ve fallen into that feel quite dark: tales about what’s stronger and deeper than whatever feels like death.