I’ve never rented a car in a foreign country. But on my recent trip to France, to see Paleolithic art in the caves of Dordogne, it would have been impossible to reach these out-of-the-way rural corners without a car. So, with a little trepidation, I rented one. “At least I know how to drive manual transmission,” I thought. Even the man behind the rental counter noted that this was “unusual” for an American.

I brought my mom to France with me, as a traveling partner. Our initial drive, from the airport in Lyon to rural France, was confusing and stressful enough that—though we drove for more than four hours—we listened to nothing but the sound of our own voices, the shifting gears, and the tires humming on the road. After several days of speeding along winding mountain roads, we felt more confident. So, as we set off for the long drive back to Lyon, we deliberated over what we should listen to.

Hungry for a particular sort of entertainment, we opted for an audiobook rather than music. As I pored through the Audible catalog, looking for something to download that was less than five hours long (and wouldn’t be too much of a conceptual challenge) I stumbled across Julia Child’s My Life in France. It wasn’t a book I was deeply excited about, but it seemed tolerable. I’ve always been mildly curious about Julia Child, though not quite curious enough to watch the movie or the show about her life. My mom agreed, though we decided that if it bored us too much, we would switch to music.

It was interesting to hear Julia recount her own initial journey into France, in the late 1950s. I learned that she had met her husband several years earlier, while they were both working positions in the institution that would become the CIA. Her husband had been assigned to a diplomatic post in Paris. He was an artist who’d been tasked with the chore of using art to make French culture more palatable to Americans, and American culture more palatable to the French. The irony wasn’t lost on me that, in the end, it may have been Julia who’d done most of that artistic and diplomatic work for him. Using her art and craft, she turned thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, of Americans into Francophiles.

Growing up, to me, French food and culture seemed like the epitome of sophistication. I suppose this was one of the reasons I never wanted to study French, in school. I wasn’t a sophisticate, so I decided to learn what I thought was a pragmatic language (Spanish). But to hear Julia tell it, France was apparently held in low esteem by the post-war waspy American elite, such as her own family. Her wealthy conservative father, who lived in Pasadena, scolded her for going off to live with those “dirty Frenchmen.”

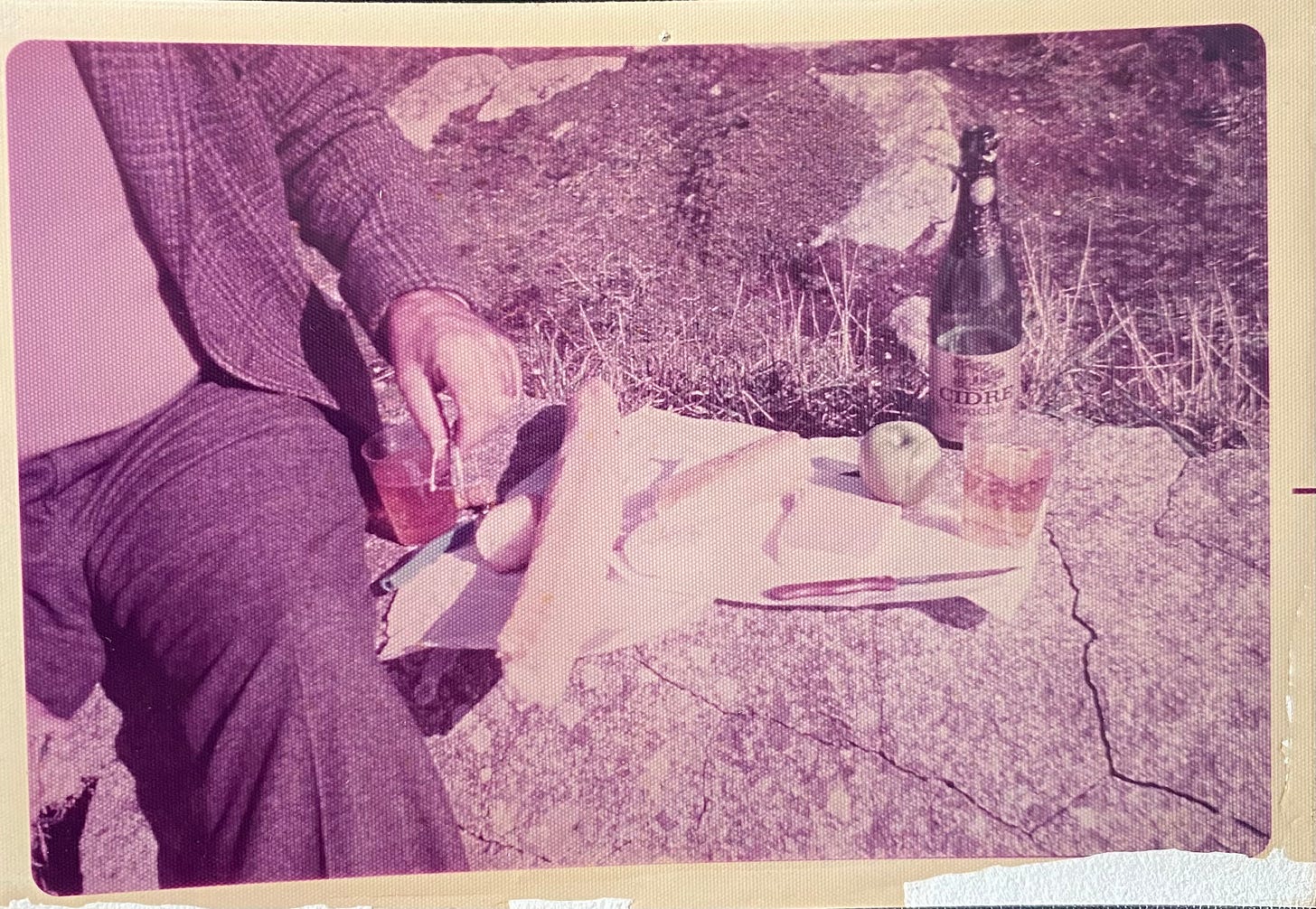

The France she entered was one that was still experiencing the aftershocks of war. She and her husband had transported their own car across the ocean, on the same ocean liner that they rode to get there. Upon landing they set off, together, for a drive through the French countryside. They saw almost no other cars. Instead, the people they saw rode bicycles, or horses. She noted that many of the children were wearing wooden shoes. Tales of this recent past that was so long gone gave me a strange feeling of dislocation as we sped along past hay bales, and fields of beaming sunflowers, in the little white Fiat that we’d booked online.

But perhaps the most dislocating thing about listening to Julia Child talk about food and France was the way it transported me into the underworlds of memory that had been stirring just below the surface, for the entire trip.

Before leaving for France, I’d been telling my seven year old daughter (who badly wanted to accompany us) stories about earlier trips I’d taken to France. As I sat in the car, listening to Julia talk about food, I realized that almost all of the stories I told my daughter were about food. Part of this is because my family is one that lives to eat. When we travel, our days revolve around the meals.

But I think there’s more to it than this. Food is a necessary part of all of our travel experiences. We have to eat. And when we eat something new or unfamiliar, we create a new channel or pathway inside of ourselves; we carve out a particular taste, smell, and texture to accompany the mental image of memory. The taste, smell, or texture of that food reactivates the memory, later on. The food becomes a vessel into the dense and murky underworld of our memory. Food acts like a material vessel to open a kind of spiritual portal. When we taste a particular food we bring specific people, specific times, and specific places to mind.

Food experiences are set up, deliberately, for tourists so that they can taste something of the feeling of a place—so that they can feel, on some visceral level, what it might be like to be part of another timeline in history, another enactment of tradition. In this way, we create the feeling of travel across time and space and we develop an intimate feeling of having participated in something beyond ourselves, beyond the perceived limits of our ordinary lives. Often this feeling is a sleight of hand, or an illusion of sorts. But the taste carves out a pathway for experience and memory regardless.

One of the stories I told my daughter was about my trip to France, at the age of thirteen. My mother and I were obsessed, on this trip, with eating crepes. We were traveling with my grandparents (my father’s parents, not my mother’s). They’d planned most of our meals, and had little interest in crepes. So, every time we had an excuse, my mother and I would sneak off to find crepes. One memory we’ve laughed about, for years, was of a careless man serving crepes from a street cart, who’d folded paper into the triangulated layers of the crepe itself, forcing my mother and I to stop in the street and refold the whole thing ourselves.

I remember that trip as the time of crepes. But I also remember that the two of us so loved these crepes because my mother made a kind of crepe—a Latvian recipe we always called pantogas that my mother had learned from her grandmother—at home. We also made the fluffy American-style flap jacks, from time to time. They were easier, and less time consuming. But when we needed a special treat, my mother made her crepes. We would fill them with sour cream, a squeeze of lemon juice, and a sprinkling of sugar—just as she used to do, as a child. In Paris, my mother studied the way that the vendors spread the batter around the pan. As we walked, and ate our street food, we would talk about her mother and grandmother who had both recently died.

All of these memories had been surfacing for me, even before we arrived in France. But I also realized, as I listened to Julia Child’s stories about France and food, how much I had been thinking of my paternal grandmother and grandfather. It was because of them that I’d traveled to France in the first place. And it was probably, in part, because of them that I was there again.

My grandmother was one of those 1960s American housewives who became obsessed with Julia Child. I don’t know how my grandmother discovered her, in the first place. Did she find the cookbook somewhere? Or did she discover her on TV? I do know that my grandmother had always been particular about cooking, and food. In the 1960s, not long after she and my grandfather had moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan (from Chicago, to attend Western Michigan University), my grandmother was featured in the local newspaper: the Kalamazoo Gazette. It was a novelty story, about the local Jewish housewife who was sharing an exotic Jewish recipe with local readers. I’m sure that she was a cultural novelty, at that time. But in the photograph they took of her, she’d set her hair like any housewife of the time. She’s standing beside her stove, in an apron, looking dark-haired, but American.

When I was a child, my grandmother’s cooking skills were mythical, to me. Every single meal I ate at her house felt like a fine dining experience. This wasn’t an accident, of course, but part of her design. We would arrive for the meal and my grandfather would have set out a cheese plate. The adults would drink wine (something they also allowed me do when I turned twelve or thirteen). There were always at least two courses, and a dessert. Most of the time, my grandmother roasted chicken. Perhaps this felt fancy, to me, because my mother and I were primarily vegetarian at home. Meat (as long as it wasn’t hot dogs) felt like an occasion. There were times when my grandmother would try something new, however. I can remember, in the early 1990s when there were not yet any Indian restaurants in Kalamazoo, she cooked us a chicken curry. It was sensational, to me, but I also remember that she expressed some disappointment at her own execution. I wouldn’t have known if she’d missed the mark.

My grandmother was invested in the domestic arts, but she also worked as a librarian. And my grandfather, who’d started his career as a shop teacher, ended up back in school to study law. He told me, later on, that his law school education had been nothing but “trade school”. But the professional change must have left them financially comfortable enough, later in life, to travel quite frequently. I don’t know how many times the two of them traveled to France, after their three sons were grown. But it became an almost yearly ritual for them. I remember that they went to other places in Europe, as well as Mexico and Turkey. But they loved France more than any place on Earth. Was Julia Child the cause? I have to suspect that she was, at least in part, responsible. My grandmother had spent decades poring over her cookbooks, and her tales and memories of life in France. I suppose that she considered France her “spiritual home”, as Julia put it

The only international travel I did, as a child, was with my grandparents, who always paid the bill. It’s impossible for me to think about France without thinking of my grandparents. And it’s impossible for me to think about my grandparents without thinking about food.

I’ve eaten enough baguettes that I can taste them without thinking of my grandparents. Although I will admit that I associate the smell of my mother’s bread baking, in the kitchen, so deeply with my childhood that I have a hard time eating bread without thinking of my mother, and the kitchens of my old homes. But when I ate my first dinner in France, and I bit into that crusty shell of bread, I had an immediate recollection of being in my early 20s and using my grandmother’s old copy of Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking to attempt to bake my own baguette.

Julia apparently worked, for years, to come up with a baguette recipe that could actually be executed in an American home oven. And the initial edition of the book also apparently instructed people to place an asbestos tile in the oven, while it baked! I’m sure that her recipe is better, and more exacting, than any other. But my own baguette was not especially spectacular. I had the right pan. And it was crusty on the outside, with a soft interior. I will give her that. But it lacked the necessary flake.

In the end, it didn’t really matter. Making a good baguette had really only been part of the point. The bigger exercise was more spiritual. I was trying to invoke my grandmother, who had been dead for years by this time. In my 20s I’d learned to cook. I’d landed a professional job, in the kitchen of a small bistro in Portland, Maine. And I found myself accruing skills that I once thought only my grandmother had. I became obsessed with cooking, and was determined to try dishes that (in my mind) only my grandmother could make. I wanted, so badly, to cook for her. I wanted her to take a bite of my food, and close her eyes with pleasure as the tastes transported her to another time and place. I wanted to see her nod at me, approvingly. I wanted to feel as if I’d been welcomed into her ranks.

Instead, I ripped open the baguette before it had time to cool and had the feeling of being elsewhere. Just as I had the feeling of being in my grandmother’s dining room, while I was really in France. And how, as Julia recounted her own memories, I realized that the fabric of my own family history had been woven from the threads that Julia—that proto-CIA agent—was selling. And I felt the absolute strangeness of being one of those Americans with money, who flies across the wide ocean on a great metal bird that burns the bodies of the dead, at this moment of history when enough of the world has stopped its wars to allow us to taste—if ever so briefly and illusorily—of one another’s timelines of history and tradition. And somewhere, in that underworld of memory, stirred that deeper feeling—one that I’ve not quite felt, not yet, not fully, not in my own body—of a time of disaster when the world shuts down and closes its doors, and the wines stop flowing, and the earth has stopped offering up all of its many flavors. But for now, that feeling is only a distant memory, sung by the ancestors, of a future past. For now, I eat. And wait.

If you’re interested, I recently published an essay in Religion Dispatches called “How Christian Theology Created the Need to Assert that Black Lives Matter”. You can find it here.