Last weekend we took my eight year old daughter to see the new Beetlejuice movie (“Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice”). We met a slew of friends at the movie theater and the lot of us filled an entire row. The kids had been looking forward to the movie all week, and when it ended they danced together in the aisle of the theater, festive and full of joy after all that haunting, to the music that ran over the closing credits.

I was about their age (a little younger) when the original Beetlejuice was released. Not only do I remember loving it, but I remember remembering it. It’s one of those movies (like “Edward Scissorhands”) that I sometimes realize is still playing deep in my mind, like a visual background music. I was struck, as I watched the sequel, that the original probably had a profound effect on my little forming consciousness. Tim Burton got into my head. Or perhaps he just succeeded in illuminating something that was buried deep in there, and in the heads of millions of other people around me. He succeeded in illuminating a potent dimension of our mythology.

It’s not often that I step back and wonder, to myself, how I acquired the strange niche obsessions that drive me. I didn’t, for instance, spend much time asking myself why I wanted to write a book about underworlds. I just started the research. But watching the new Beetlejuice movie did make me consider the possibility that Tim Burton, and his underworlds, are somewhere at the genesis of my obsession.

The underworld, in the Beetlejuice franchise, is both ancient and modern. It pulls from the ancient past, and infuses it with something distinct to our own moment. One of the things I found alluring about it, as a kid, was that it offered me an image of the afterlife that was nothing like the sort I’d heard others try to sell me on. I’d heard rumors of both heaven and hell; those rigidly opposed dimensions of bliss and damnation. But something about that, I’m still not sure why, never smelled quite right to me. Even as a small child. I suppose that what felt real was the reiteration of something more actual: an ambiguous domain where goodness and evil, chaos and order, are in much closer contact. That’s the afterlife that Burton presents us with.

Like the Ancient Egyptian underworld, Burton’s underworld feels difficult to penetrate. It’s not necessarily a place where judgement feels imminent, as in the Egyptian variant. But it’s certainly thick with obstacles. They’re just a much more modern sort: waiting rooms, long lines, tickets, passports. There’s a lot of administrative layers to it. It’s a great cosmic waiting room.

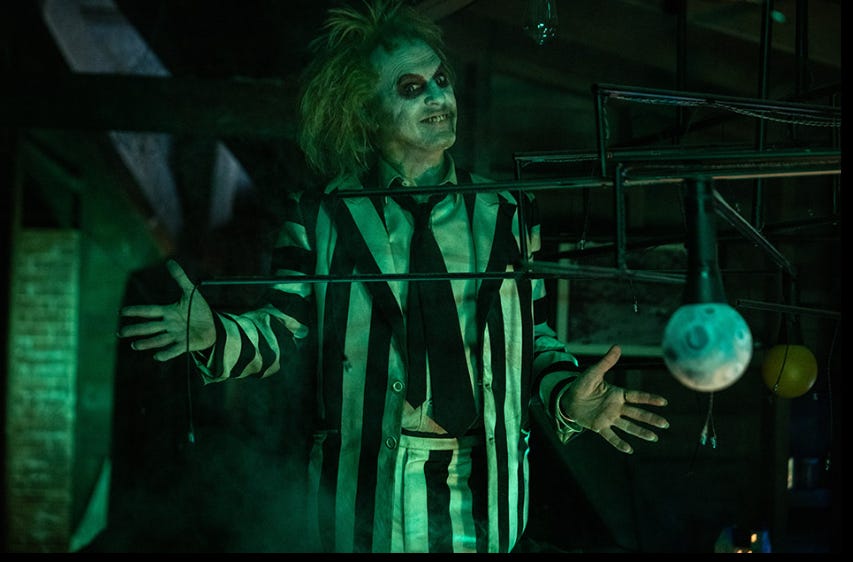

Like the Ancient Greek underworld, Burton’s underworld isn’t just a zone of punishment and torture. It’s not a hell. There are hellish spaces in his underworld, just as there was Tartarus in the Ancient Greek underworld. But there are also places (like the platform to the “soul train”) where you can party, dance, and enjoy yourself in a way that feels rather innocent. And while it’s not an especially beautiful space (the crooked ceilings and passageways seem designed to offend our desire for order and symmetry) it is festive in its way. It has a sleek noir aesthetic, though the black and white checkerboards and stripes also give it a chaotic air of fun.

It’s especially in this, the more Greek sense, that Burton’s underworld feels a bit resistant or countercultural. The amplification of these Greek flavors of the afterlife seem to be specially designed to foster skepticism about the afterlife stories that have become so familiar to us. I’m talking about those visions of the afterlife that, over the course of Christian history, have come to feel almost like features of natural history. When I speak, with my students, about “the afterlife” in generic terms, they speak back to me about “heaven.” And when I tell them about cultures in which the dead reside in an underworld of sorts, they see this zone of lifeless ambiguity as nothing other than a hell.

Losing the bliss of heaven makes anything less saccharine look like torture, I suppose. But Burton’s underworld is designed to make a mockery of the binary logic of this more familiar Christian afterlife. He pulls from ancient visions of the underworld in order to do so, but what he offers is also modern.

I think it’s also important to note that Burton’s underworld carries a dimension of comfort with it—strange, ugly, and chaotic as it may be. I tend to imagine that this has always been the case with underworlds of all sorts (ancient as well as modern). You just have to know what sort of comfort to look for.

It’s clear that, in Burton’s cosmology, the living and the dead aren’t meant to interact with one another directly. In the new film there’s a squad of police who patrol the boundary between the living and the dead, to ensure that there’s no contact. But this is because the line itself is actually rather easy to cross, the boundaries are easy to violate. The line between life and death is not always clear. The underworld isn’t life, but it doesn’t lack for some dimension of pleasure and entertainment. The dead long to be living. But the living also long to be with the dead. In the end both the living and the dead seem to want the same thing, which is togetherness. There’s a kind of comfort in this shared desire for an enduring togetherness, even if it’s also prohibited.

I think the comfort of an underworld like Burton’s probably feels more accessible to many of us today. We live in a world that’s been stripped of enough supernature that miracles feel unrealistic. But there’s still enough supernatural residue left to make us acutely aware of the fact that things are always so much stranger than they seem. We might not believe that our loved ones are in “better place”. But it’s easier to believe that they’re still with us. We can sense their presence, if we really try. So, Beetlejuice is for a certain kind of believer.