“Without Man and Nature, all creatures can come back to life.”

ANNA TSING

I’ve always been drawn to Baba Yaga. I remember believing, when I was little, that I was related to her somehow: that she was actually a (distant and long dead) member of my own family.

I was close with my family, on both sides. I was lucky enough to know not only both of my grandmothers, but two of my great-grandmothers (the mothers of my grandmothers.) I was a little afraid of them. But I also had an unshakable admiration and respect for them. My sense was always that they were to be mostly admired, and a little bit feared.

I was comforted and mystified by their papery flesh and their soft bodies, their habits and behaviors that seemed to be entirely in disregard of all social conventions or niceties: their refusal to hide irritation, the weathered dresses they wore on repeat, the beaten dusty slippers they shuffled in, their half-eaten eventually discarded meals, their hidden tins of hard candy, thin crowns of hair that seemed permanently disheveled, the skin around their eyes that seemed determined to draw itself ever closer to the ground. Their rhythms and preferences and cycles were unlike those of anyone else I knew. This, in itself, was wondrous and awe-inspiring. I couldn’t imagine becoming like them, and I couldn’t imagine them having ever been children. It pushed my imagination too far.

They clearly enjoyed having me nearby. But they never seemed to want me around for very long. Unlike my grandmothers, they didn’t watch over me, or cook for me, or entertain me. I heard stories of things that they once cooked, but I never tasted any of these dishes. Indeed, some of the recipes relied on things—like a tub of chunky lard by the stove—that no one I knew used anymore: things that had long passed out of culinary fashion in America.

Every thing my great-grandmothers did seemed consequential, archaic, mysterious—and, for all of these reasons, also sacred and holy. No Shabbat blessing of the candles will ever seem so holy to me as the one my great-grandmother Thelma performed in the tiny dark kitchen of her little retirement cottage in Tampa.

One of my great grandmothers—Anna, who we called Omite—was Latvian. I never had a real conversation with her, despite the fact that I knew her for thirteen years (until she died, just shy of 100). She learned to speak Latvian, Russian, Polish, Czech, and German. But, by the time she emigrated to the United States in 1957 she was already sixty-two years old, and she couldn’t be bothered to learn another language. Our communications were always mediated, typically through my mother. Her entire lifeworld was a mystery to me.

Omite liked to eat things that I found unsettling, like caviar. She had no stories to tell me, about her past. It was all left up to guess work. But I knew she’d spent most of her life in Latvia. Much of this time she’d passed in the countryside, where my grandmother had told me many stories about their summer cottage in a small village not far from their home in the capital, Riga. I believe that my grandmother Maiga also drew sketches, inspired by these woods, for a Latvian children’s magazine that she created art for. I knew something about my grandmother’s relationship to those woods. But my great-grandmother’s relation to the woods was a mystery to me.

For all I knew, she could have had another little secret house in the woods, on chicken feet.

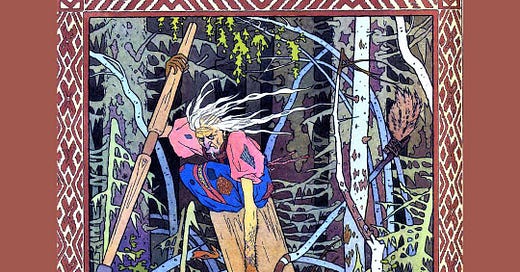

It’s not that, when I discovered Ivan Bilibin’s illustrations of Baba Yaga on my mother’s bookshelf I thought of my great-grandmother. But it did seem to me as if she could have been someone that my ancient great-grandmother had known. Maybe some distant aunt, who lived in the woods. My great-grandmother—I knew, without asking—had seen many terrifying things. She lived through a war, and became a refugee. It seemed believable, to me, that she could have also seen the face of Baba Yaga.

So, I felt connected to her—Baba Yaga, this old woman of the woods. I understood that she was fearsome. But this didn’t make me dislike her. Rather, it gave me a particular sort of respect for her. I had been primed to feel a deep respect for the faces of older women who scared me a bit. It may have stretched my imagination, to see myself in them. But I knew that reflection was there, somewhere.

These ambivalent, curious, feelings for Baba Yaga have always been there. And I’ve never quite understood them. But I stumbled upon some new information about Baba Yaga, researching the fungal dimensions of underworlds, and I’m starting to unravel some of these old mysteries. Or perhaps I’m just immersing myself in them.

Guardian of the Underworld

In Chanterelle Dreams, Amanita Nightmares: The Love, Lore, and Mystique of Mushrooms Greg Marley mentions—as a brief aside—that Baba Yaga was often featured in illustrations with mushrooms because she was also, often, understood to be a guardian of the underworld. Many Russian folktales, Marley notes, imagine that the path to the underworld runs through the forest. And one of the things that makes Baba Yaga fearsome is her ability to live in the woods, by herself. In Russian folklore, he notes, mushrooms often possess a magical character, and sometimes serve as food that’s intended for the dead. Baba Yaga knows the secrets of the mushrooms. She knows how to use their magic, and she’s immune to it.

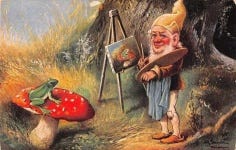

The mushroom she’s most often depicted with is the lovely fly agaric toadstool, or Amanaita muscaria, which is also notoriously poisonous. It’s inspired many charming fungal illustrations in children’s books and cartoons, as I’ve been reminded of since having a child. It’s a mushroom that encapsulates the twin powers of beauty and fear that fungus often invokes in our human lives. Mushrooms can nourish and poison us. They are, in many ways, icons of ambivalent power.

As Andreas Johns illustrates, in Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale Baba Yaga herself is an ambivalent figure. While always fearsome, she can sometimes help the protagonist of a story. Other times, she plays the role of a narrative villain. Like mushrooms, she’s an icon of a power to be feared and admired. This is why she’s surrounded by a fruit of the woods that, perhaps, only the dead can eat.

Icons of Indeterminacy

Baba Yaga, for me, is an icon of intimacy with uncertainty and indeterminacy. She is picture of what a face of uncertainty might look like. For this reason, I think, it’s entirely suitable that mushrooms are her consort. As Anna Tsing has put it, in The Mushroom at the End of the World, “indeterminacy has a rich legacy in human appreciation of mushrooms.” I suspect that it has its legacy in Baba Yaga appreciation, as well.

It also makes sense, then, that mushrooms and fungi have branched their way into our cultural imagery and subconscious in recent years. As a painter whose fungal watercolors I was admiring on the streets of Edinburgh recently put it (when I complimented her), “fungi are so hot right now.” We are living in precarious times. Some of us are exposed to more precarity than others. But, in the face of climate change and its multifarious forms of impact, we are all precarious. We all face, says Tsing, “the imaginative challenge of living without those handrails, which once made us think that we knew, collectively, where we were going.” Tsing finds, in fungi, a model for surviving in precarity, and an image of the pleasures that might still be had amidst the terrors of indeterminacy.

Baba Yaga lived in a house that had feet that could walk, and no handrails. She hovered between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Her world was human and more than human. She was an old woman, living alone in the woods. Was she driven there? Did she choose to live there? Was she born an old woman, in that forest place? Or does she have a history? Whatever the case, she lived fiercely into her precarious life.

The world she learned to inhabit was beyond the world of Man: she was witchy, or even more than witchy. She did not follow the rules of (patriarchal) civilization. And her world, while forested, was also magic. It was beyond Nature. It was ungoverned and ungovernable. Perhaps, in this sense, she is also an icon of the indeterminacy beyond Man and Nature, an icon of the possibility that—as Tsing puts it—“without Man and Nature, all creatures can come back to life.”